#8 The Power of Vision – Fred Hollows

What does it take to improve the lives of millions of people? The late Fred Hollows knew. He was known across the globe for his groundbreaking work in disrupting the global medical establishment, and his legacy lives on among the doctors he inspired. His most famous student, Dr Sanduk Ruit, has helped bring sight to over 125 000 people and trained thousands more doctors. In the process, he has directly improved the lives of millions of people. But what does it take to achieve transformation at this kind of scale?

Click the play button above to stream it here. Or listen to the episode on PodcastOne, Stitcher or Apple iTunes.

Or use any Podcast app with our RSS Feed).

Full Transcript of Episode 8 – The Power of Vision

HOST: I want you to slowly close your eyes, and imagine for a moment you’re going blind. The world around you is closing over.

HOST: Now imagine you live in a country that isn’t rich enough to provide even the basic services required for the needs of the blind.

How would you get around? How would you go to school? Or work? How would you feed yourself? And your family?

Today on Changemakers, the remarkable story of a surgeon – who has personally operated on thousands of people, saving each and every one of them from a life of darkness and hardship. And the kicker is: that’s not even his greatest achievement. Let’s go.

HOST: When he was about seven years old, Tran Van Giap was playing with some kids in his village in Vietnam. They were mucking around as seven year olds do.

GIAP: One of the kids, one of the kids accidentally throw a piece of glass basically to my eyes.

HOST: He was rushed to hospital but it was no good.

GIAP: So my right…the right eye’s…could not see. At all.

HOST: Still his parents did not give up.

GIAP: I was very lucky to have my family at the time to support me through my eye injury, taking me from hospital to hospital. But even then, this wasn’t enough.

HOST: Being blind in one eye didn’t just make it hard for Giap to play with his friends. It made it impossible to go to school. His school was simply not equipped to deal with a child who was half-blind.

GIAP: I didn’t go to school for more than a year…because of the issues.

INTERVIEWER: So this, this was clearly going to threaten your future, having this eye injury.

GIAP: It’s not only the physical…pain and incapability that I was facing at that time. It was also the psychological distortions…that I had to face to go to school.

HOST: One day, a year after the accident had happened, Giap’s father took him to a popular local hospital. The best hospital in his entire region. If anyone was going to be able to help Giap, they would be here.

HOST: The hospital said there was nothing they could do.

GIAP: So my parents, my dad in particular, took me to Hanoi to seek further help.

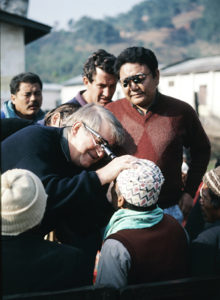

HOST: There they went to a makeshift eye clinic. There was a long line of children, waiting to have their eyes examined. One of the doctors was a foreign-looking man, with a big bushy mop of silver hair.

GIAP: And this is when we stumble across Dr. Hollows, when he was with other doctors at that time examining other children’s eyes.

HOST: Dr Hollows. Dr Fred Hollows.

GIAP: So my dad pushes me towards the line.

HOST: Unfortunately, the hospital had limited resources. Their policy was they couldn’t just operate on every poor child who turned up half-blind, even if it was taking him out of school, and affecting his whole future.

GIAP: So according to policy at that time, there was only one older person and one younger person allowed to get the free surgery for the eyes at a time.

HOST: Giap’s father put Giap’s name down, hoping to be the lucky pick. He wasn’t.

HOST: Then, in a stroke of incredible luck for Giap, the boy who had been selected for surgery didn’t want to go through with it.

GIAP: And even though I wasn’t the first one to be chosen, the first kid forfeited because he was scared.

HOST: Giap’s dad leapt into action. Pressing the doctors to selected Giap instead.

HOST: What sort of cruel lottery was it that Giap’s future could hinge on an arbitrary decision by a doctor, enabled only by another kid’s reluctance to go through with a medical procedure.

GIAP: And that’s when I finally met and, you know, talked to Dr. Hollows. And he was kind, and…I remember perfectly everything that happened that day. How his eyes looked at me and how scared I was because I never really come in contact with foreigners before. And…that was the guy that saved my life.

HOST: Giap’s eyesight was restored, he returned to school, and became a diligent student. From his perspective, he’d been given a second chance, and he wasn’t going to waste it.

But in places where resources are sparse, for every happy story, there are many more that don’t have a fairy tale end.

Take for instance, Sanduk Ruit, who was 15 and living in the foothills of Nepal, when his sister became ill with tuberculosis. Although it was treatable, her family couldn’t afford the medicines required. The doctors said there was nothing they could do.

Meanwhile, Sanduk’s father had noticed that he was a bright kid, and arranged for him to go to the local school. But it wasn’t just around the corner.

SANDUK RUIT: was somebody who I was sent you know from my village to the school that I went to was almost about 15 days walk a real 15 days walk. There were no schools in between. And so that’s where I went. [16.6]

HOST: A 15 day walk. That was his local school.

For six months, his sister convalesced, but just as they thought she was getting better, things took a turn for the worse. Sanduk came home.

SANDUK RUIT: I saw her pretty much very thin and cataracts really you know. And so I was it was a very sad moment for me very sad to see her in a in a condition like that.

HOST: Within months, she was dead.

SANDUK RUIT: My father sent me to a small boarding school and so I managed to have this toughness in me from early on I didn’t really get that that fatherly or motherly closeness and whatever I got in terms of family was the closeness and sentimental relationship that I had with my sister and that that was something very strong bond and you know her death was a big blow big blow for me.

HOST: The total lack of adequate medicine had taken from him his sister.

SANDUK RUIT: It really hit me very hard for a few months and then I started really thinking very hard and saying that maybe this is the branch this is the future that is inviting me to properly take up medicine and see whether I can be useful to many of this, ah, people who need medical treatment in my country. So that was really an inspiration that made me take medicine.

HOST: And that is when Sanduk Ruit – a bright 15 year old Nepalese boy – decided to become a doctor.

HOST: Of course, nothing is straightforward. Unfortunately, almost immediately, Sanduk’s plan ran into trouble. First off, his schooling got cut short, thanks to a war.

SANDUK RUIT: I couldn’t complete school there because India and China started having war in the 1960s and all the schools were shut down.

HOST: Eventually Sanduk got a scholarship to complete his education in another school. But when he announced he wanted to go to medical school there was just one small problem.

SANDUK RUIT: Nepal didn’t have any medical school.

HOST: And so instead he travelled to India and did a medical degree, and then returned to Nepal.

SANDUK RUIT: And Nepal was one of the first developing countries to have a proper statistics on the magnitude and distribution of blindness. And I was very lucky to be part of a junior medical officer at that time and I had an opportunity to go into very remote areas accompanying senior ophthalmologist. And this was in one of those trips that I accompanied one of the senior ophthalmologist to the west of Nepal where in one particular rural surgical set up I saw him operating about four children in the family you know of cataracts congenital cataracts. And that evening after the everything was finished I started really thinking you know is just a branch where in such a short time you can make a difference to so many people’s life.

HOST: By now, Sanduk was a doctor specialising in eye care, completing the final stages of his training through a series of residencies. And in Nepal, his skills were in high demand.

SANDUK RUIT: So prevalence of blindness was about 1 percent. Yeah. And. The interest that I had was right on that beginning on cataracts.

HOST: For those who don’t know — and I didn’t when I began this story, cataracts form when the normally lens in your eye becomes cloudy. It’s a bit like the way a car windscreen fogs up on a cold morning. The only way to deal with it, is to remove the lens, and replace it with an artificial intraocular lens. Although it sounds icky, it’s actually a simple procedure, but the replacement lenses were about $150-200 at the time. In places like Nepal, they couldn’t afford the intraocular lens, and weren’t trained to do the surgery, so instead they just removed the cataract by removing the eye’s entire natural lens, with the result that patients ended up ridiculously far-sighted.

Aware that this was a problem, authorities had begun collecting detailed statistics in Nepal, and what it showed was shocking.

SANDUK RUIT: And the statistics told us that the type of cataract surgery done those days. Not only in Nepal but all the developing countries and even in some of the developed countries in rural areas were taking the cataract out. …And if you remove the cataract only you can barely count fingers in front of you.

HOST: The result was that patients had to wear ridiculously thick glasses just to see, and even then, a simple task like walking around was difficult. As he travelled around, more than 60% of the cataract patients that Dr Ruit visited, had abandoned their glasses. The surgery was essentially useless for them.

But that wasn’t the only problem.

SANDUK RUIT: 5 percent cause of blindness was bad cataract surgery.

INTERVIEW: Geepers.

SANDUK RUIT: Bad cataract surgery.

INTERVIEW: The doctors were part of the problem.

SANDUK RUIT: Yes. Yes. It wasn’t like that because cataract surgery were those days and done without magnification. We could just you know we were doing it with reading glasses and torchlights you know it was.

HOST: So basically only 30% of cataract surgery in developing countries restored sight. Whereas in the West, pretty much every procedure restored sight.

SANDUK RUIT: You’re just making giving them navigational vision that’s all. So that was the situation in mid 80s.

HOST: So, inspired by the surgeon who guided him through his residency, Dr Ruit, started treating patients.

INTERVIEW: So when you first started working as an eye surgeon how many people did you treat per year.

SANDUK RUIT: As a young doctor I would say I was pretty aggressive and used to see about I would say about 100 patients a day.

INTERVIEW: Oh my God! A day!

SANDUK RUIT: Yeah. And maybe those days like again we were all doing the surgery. That was that established those days you know and doing about 20 25 cataracts per day.

HOST: But even with all that surgery they still couldn’t afford the intraocular lenses that would make it so much more effective. Dr Ruit says he was troubled but didn’t know what to do.

SANDUK RUIT: I was trying to talk to you about all the frustrations and barriers of not being able to provide the kind of surgery that I have heard about. And for these people where these people are having so much unsuccessful they are not seeing after the surgery. And what are barriers and things like that constantly in my mind.

HOST: Then one day, he was sitting have a cup of tea with a friend of his, who happened to be the head of the World Health Organisation in Nepal. The friend mentioned he was about to go and pick up someone from the airport, a doctor.

SANDUK RUIT: So he said. If you are free why don’t you come with me…

HOST: So they head to the airport.

SANDUK RUIT: Normally when we go and we have this we used to have this thing in our mind that the World Health Organization consultant you know normally comes pretty much dressed up in a suit and ties. And probably those days They’re was to carry a little briefcase in their hand. And then there was nobody that we could find it was sort of fitting into our description.

HOST: Remember, this was the mid-80s. There were no mobile phones. They assumed the man they were looking for had missed his connection.

RUIT: So as we were about to leave and we get a we get somebody shouting at us are you folks looking for me you know. So we turned around and looked at this gentleman looking pretty you know sort of rough. And finally. He says, I’m Professor Fred Hollows, you know. And so that’s how we met.

HOST: Professor Fred Hollows. If you come from Australia like me – you’ll know who he is. He was a larger than life character, known as a prodigious drinker and extraordinary raconteur – as well as a prolific eye surgeon.

Like Dr Ruit, Professor Hollows had fallen in love with the transformative possibilities of eye surgery, especially for the poor. He ran his own eye clinic in Sydney and had scrambled the resources together to create mobile eye clinics throughout the outback and central Australia, catering to indigenous Australians.

But Professor Fred Hollows was not in Nepal to look at cataracts. He was working on trachoma.

SANDUK RUIT: What is interesting to me is he was doing work on trachoma. He came into this space he saw and talked to you about the fact that the big issues were cataracts and he and he changed his focus. Did he did. He did. How important was listening to his work. You know he was exceptional in numbers. He was very good in what we call it that epidemiology.

INTERVIEWER: Really. I mean the fact that he listened to you not everyone listens right. Of course you know some people have a plan. They just want to roll it out better. Fred Hollows didn’t seem to do that. No. Why do you think he listened to you.

SANDUK RUIT: I don’t know. I don’t know. But there is you know he there were certain certain feelings that I got that this man is genuinely interested in listening to me.

HOST: Almost immediately, something clicked. Even in the car on the way back from the airport, Professor Hollows and Dr Ruit got talking. Soon, they were plotting. For the first time in his life, Dr Ruit found someone who was interested in hearing all the frustrations that he was having treating cataracts. The lack of equipment for doctors doing the surgery, the lack of training in the technique and the prohibitive cost of the lenses that would actually make the surgery just as good as what was standard practice in the West. Professor Hollows invited Dr Ruit to come and check out his practice in Sydney Australia, and also to see his mobile surgery in Central Australia. There, they kept chatting.

SANDUK RUIT: Fred and I used to sit over a glass of whisky in the evening and we used to sort of think about how we could do in intraocular lens surgery in a developing country when there is no other sources what microscopes to use how much the microscopes was going to cost how much the lens is going to cost what fluid do we use to wash the cataract. Other fluids that are available in present time are they safe enough. What are the results going to be. What needle to use. How can we do that for 50 cases. How can we do that for 100 cases. So all those questions we started asking ourselves [42.0]

HOST: It started consuming Dr Ruit’s life.

SANDUK RUIT: But as I started I started dreaming about the surgical procedures. You know I started really and then I used to recollect how the tips of the surgery that I was thinking about and started coming into my dreams. So it was very interesting. HOST: Eventually, it was time for Dr Ruit to go back to Nepal.

SANDUK RUIT: Fred give me a couple of intraocular lenses to take back. I think it was about 40 intraocular lenses.

HOST: Fred and Ruit set up an organisation called Nepal Eye Program Australia.

SANDUK RUIT: And that that raised the first one in fifty dollars that I could buy some instruments with that.

HOST: So armed with 40 lenses and the right equipment to do the surgery, Dr Ruit headed back to Nepal.

SANDUK RUIT: Two things I realized I knew I had to work very hard to fight with the establishment. And I to come out with a very smart system that the world was going to believe.

HOST: No biggie. Reinvent eye surgery in the developing world, while fighting the existing medical system. The first thing he had to do was work out how to refine the surgical equipment so that it could be used in a mobile set-up, without the fancy luxuries you get in an operating theatre

So we start it with a small team. We started doing mobile surgery as you know cutting our own microscope small different types of microscope practicing with different and different places and donated ocular lenses and sutures and other resource materials and doing. 100 there. 70 there and then refining on the technique.

HOST: It was the same method that a silicon valley startup might use. Launch, learn and then iterate. Eventually, Dr Ruit felt he’d perfected the technique.

SANDUK RUIT: So I said Fred I’ve done about two hundred it’s a very successful extra cases with the intraocular lengths implantation and the results look fantastic. So where did you do it. Is it in eye camps. Shit then I must come and look at it.

HOST: A few weeks later, Professor Hollows arrived, and asks to see the new techniques being used.

SANDUK RUIT: I had to demonstrate to him about 150 cases. He saw how the surgeries were being done and he saw the results. The second day we were I tell you we were drinking the whole night.

HOST: It was a triumph, but there was a problem. By now, the medical establishment had gotten wind of what Professor Hollows and Dr Ruit had been doing in Nepal, and they weren’t impressed. They thought Fred and Dr Ruit were endangering their patients by setting up mobile clinics rather than using established operating theatres. In short, they thought Hollows and Ruit were a couple of cowboys. It was decided that all the major players in eye surgery would meet in Nepal, to nut it out.

SANDUK RUIT: The who’s who of Ophthalmology I call the mafia as you know. They came and attended the meeting all big shots from America from each other from WHO from India and Pakistan from Sri Lanka Bangladesh this presentations were made on thousand cases of successful intracapsular surgery.

HOST: That was the old fashioned surgery, that left people ridiculously long sighted. A method that had already been superseded in the West by intraocular surgery.

SANDUK RUIT: Two thousand cases. And the sheer amount of IPB who was an American said this is a time tested successful method. We should continue to follow this.

HOST: Then Dr Ruit got up to present his new method that left people with much sight.

SANDUK RUIT: And there we stand Fred and I stand we present 150 cases I mean our ocular lenses done in the bush. Do not accepted. We were virtually made to sideline as an outlaw.

HOST: In essence, the medical establishment were saying that change was not possible. That the developing countries would have to put up with second-rate outcomes. It was a devastating blow.

Back in a moment.

HOST: At the global conference of eye surgeons in Nepal, Dr Ruit and Professor Hollows had been told that their new, safer form of surgery, that restored sight and meant patients weren’t required to use unwieldy thick glasses for the rest of their lives, had not been adopted as the new standard.

Fred Hollows could not accept that.

SANDUK RUIT: He got up and. And then said. You guys must listen that right now. WHO is providing thick glasses in the back of surgery will one day put an intraocular lens on that.

HOST: The problem was, before they could spread their methods to other countries and train surgeons in their new technique, they needed the medical establishment behind them.

SANDUK RUIT: I had to virtually write papers and international journals and gather a lot of other friends an international community invite a lot of other people to come and watch what I was doing. And convince people that this is correct.

INTERVIEWER: So you had to train you know the people above you before you could train their surgeons. Definitely. Oh definitely.

SANDUK RUIT: Definitely definitely. This was this was hardly accepted.

HOST: Slowly the tide of opinion started shifting in their favour. The evidence was undeniable. But that wasn’t their only problem. In many way, they had a bigger problem: the intraocular lens crucial to the surgery was expensive.

SANDUK RUIT: When we started at that time intraocular lenses there were that used to cost about 150 to 200 dollars.

INTERVIEWER: why was that a problem that they cost 150 dollars.

SANDUK RUIT: You know doing a spending one hundred fifty dollars twenty dollars per case was it would be impossible for us to make it as a make a public health program. We can only do that for patients who could pay for it and there were just handfuls.

HOST: In other words, it was great that Professor Hollows was able source some lenses from Australia for the trial, and they’d managed to get a few more donations here and there, but it would bankrupt any Third World health system to provide those lenses themselves. Until they could reduce the cost of the lenses, affordable eye surgery would remain the preserve of the very rich and the very lucky in the developing world. Hardly a basis for a public health system.

But Fred Hollows had a solution. Rather than importing expensive Western lenses, why not set up a factory in Nepal?

According to Dr Ruit, Fred talked about it incessantly. He could see that it was the only lasting solution. His plan was to build factories in Eritrea and Nepal, to radically reduce the cost of the lenses. Fred raised money from fellow Australians and work started on building the factories.

HOST: Unfortunately before he could see either factory built or hold one of the intraocular lenses in his hand, Fred Hollows passed away. It was now up to his successor Dr Ruit and the growing team around him to make Fred’s vision come to reality.

SANDUK RUIT: So it was for us to look at the bricks and the walls and the equipment and everything. He cast just a vision. Yeah. Guys had to put into action. So it was very difficult very difficult going through the intricacies of technology and one technology not working and about bringing in technology. So it was a difficult thing.

HOST: A year after Fred Hollows died, the first factory came into operation.

RUIT: The first year when we started manufacturing about 30000 leonsis a year the cost of the lenses were 15 dollars for one. The second year we started manufacturing about 50000 a year. The cost of the lenses would come down to about seven dollars. And fourth year onwards when we were starting to manufacture about 200000 a year the cost of the lenses that come down to four dollars.

INTERVIEW: Oh my God.

HOST At that price, the lenses were truly accessible. They would be able to distribute them to the entire world.

HOST: At the same time that Dr Ruit and Professor Hollows were imagining a factory for lenses, they were trying to work out how to solve the other major issue: how do you roll out a new surgical method across the entire global South.

SANDUK RUIT: Second story a very important story is training lots of people lots of good doctors and technicians to conduct this in other parts of the world.

HOST: The problem was that in country after country that Fred and Dr Ruit visited they came up against a medical establishment stuck in their ways of doing surgery. Ways that were often imported from much richer countries.

Just before he died, Professor Hollows made a commitment to train 300 Vietnamese surgeons. But there was a problem. Professor Hollows was sick, and had been hospitalised. So he checked himself out of hospital and traveled to Vietnam with Dr Ruit.

SANDUK RUIT: And those days the Vietnamese they believed in using the French Pax French system the French system used to actually an American ophthalmic pack’s very expensive you know disposable packs that they thought to do it in try lens surgery. They thought that was one of the mandatory things to do because that’s what that’s what the French taught them. And using those packs was very expensive. One pack for a patient would probably cost you a thousand dollars per patient.

HOST: They had two days to convince a group of skeptical doctors that his techniques were the way to go.

SANDUK RUIT: We had to first convince that our technique is correct so demonstrating couple of surgeries in the first half and then using the same disposable packs we didn’t want to hurt them. And slowly by lunchtime we gathered a little bit of confidence from them in terms of what we were doing. So we’re using part of the disposable packs part we were using non disposable packs. And what makes that is he was let them see the results tomorrow. Then you’ll have them in your hand.

HOST: One of the surgeons that Professor Hollows trained was Dr Phan Binh. He says that one of the things they emphasised was the sheer quantity of surgeries you could do with this new technique.

DR BINH: He said that with the old technique…a, a surgeon could perform around 10 cases per day, because it takes around 30 minutes to do a case. To do one operation. While the new technique, with the new technique, an ophthalmologist could perform around 30 cases per day. And it takes them around 10 minutes for each case.

HOST: Dr Ruit and Professor Hollows decided the best way to teach this was by doing.

SANDUK RUIT: So when about 50 cases we did that day. And for them that was a very big number. They would never see anybody coming from outside experts coming from outside. There were probably five or six cases per day. And that kind of number was. So they were saying you know we don’t have to see the results the complications and results.

So anyway the next day when the patients were seen. And luckily most of the patients had very good results. And they were they were totally taken aback by the results. So we had them in our. Really. So we started doing the way we want it now. We started virtually using non disposables. And you’re seeing and seeing them that it is possible to use cost effective appropriate technology and still deliver competitively better results than you expect. Can I. Yeah. It sounds Your method sounds it has some showmanship. You could.

INTERVIEWER: The method sounds it has such showmanship. You could do five to 50 operation. Is that part of how you were able to make this radical change. Do you think?

SANDUK RUIT: You know we have to lobby we had to lobby and we had to demonstrate that it is powerful it could do better it could do more. And you know we started out as underdogs.

HOST: The demonstration left a lasting impact on Dr Binh. But Professor Hollows knew it would fail if all he did was teach the new technique.

INTERVIEWER: So, when Fred Hollows came to Vietnam, he not only changed the technique but he also set up a training system for, for doctors. Is that right?

DR BINH: es, absolutely. When Fred Hollows came to Vietnam, he didn’t have much time left because of his illness, so he aimed to create 20 new doctor trainers. And he wants to set up the training system so that the Vietnamese trainer could train others.

INTERVIEWER: How many surgeons have you personally trained, Dr. Binh?

DR BINH: So I personally trained around 50 surgeons.

HOST: And remember, each of those surgeons has in turn, brought eyesight to literally thousands of people. That’s a lot of happiness being created.

DR BINH: Even though I have done 1,000 or 2,000 cases the 2,000th case still brings the same feelings of ecstasy. There was one time when I operated on one man, he was blind for so many years and after the operation I followed him back to his home, but he wouldn’t go into the house immediately he just went around touching everything, he touched the cow, he touched the bricks and everything, because all he could do before was touch but now he wanted to touch and see at the same time.

HOST: So Dr Ruit spread his technique to Vietnam, and then Pakistan, India, as well as countries across Africa, building a lens factory in Eritrea, and training surgeons how to train other surgeons along the way.

INTERVIEWER: How many surgeons have you personally trained.

SANDUK RUIT: I think I’m now from people who have been sitting closely with me for a few days to have spending a few months you know. But there must be more than thousand.

INTERVIEWER: My understanding is that it’s more than that

SANDUK RUIT:: More than that, yeah.

SANDUK RUIT: I mean what’s really nice is you know I don’t know what would you call this but we had a we had a French doctor who was an Marché and he came to going to lunch that system and he was there for three months and he learned the whole package and to get back to the French speaking Africa. And he went on to train more than 600 African doctors. Not only that but his he has institutionalized the system in the university in Cameroon. This is just an instance of how you know how these are scalable how they are replicable. I think these are these are very powerful very very powerful. They do nothing except good for a large number of people.

HOST: When you hear visionary stories, so often the logistics of how something was achieved gets brushed aside as the shining outcome becomes the point of focus.

The wonderful thing about this story is that it’s all about the practicalities.

Sanduk Ruit and Fred Hollows took the world as it is, and shaped it into what it should be, using techniques that could be applied to any problem.

Changing the surgical technique localised the way of doing things, making their method superior to the existing system.

Reducing the cost of the lenses, minimised the reliance on Western benevolence.

And training the trainers allowed their revolution to scale up and spread rapidly across the global, bringing sight to millions of people. But above all it allowed them to harness the biggest resource available to them — the local talent.

A more showy approach might have missed the details. But the transformation was in the details – the wasteful use of disposable equipment, the unsuitable surgical techniques imported from the West, and the arrogance of the medical elites who were happy for substandard outcomes to be the norm for those poorer than themselves.

INTERVIEWER: Well I mean Fred my understanding as you say talk about teach. Teach a man to fish rather than give him fish and you feed him forever.

SANDUK RUIT: He he said that we have taken that further. Yeah. We teach them how to sell the fish fishes and make money out of it and buy more fishing rods.

SANDUK RUIT: And this is this is where the idea is is a is a great business model. And it needs radical change. It is. It does. It does. People can see it as it.

How many people do you think that this Fred Hollows is work in your work. How many people do you think can see because of that now. I mean you know the basic straightforward I would say is you know between us and Asmara we produced about 8 million intraocular lenses. That’s just the basic. And you know on top of that maybe few more millions.

HOST: The Fred Hollows foundation is continuing Fred’s work 25 years later training doctors, nurses and health workers around the world.

Join our weekly email list to hear our latest musings, podcasts and training. Click on this button to subscribe: