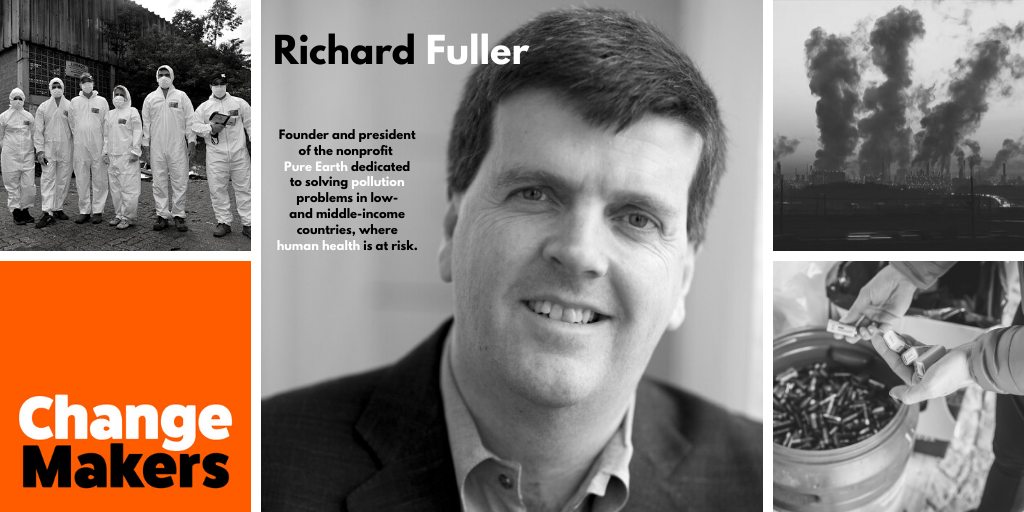

Richard Fuller – Change Maker Chat

What happens to the communities that suffer from toxic pollution? Too often nothing. But not if they partner with Pure Earth, the world’s only global NGO working on toxics. Today we talk with it’s founder Richard Fuller – engineer turned toxics crusader who has helped lead an intervention that has cleaned up over 120 places. We find out how he got into it, and how Pure Earth works with communities to create lasting change.

Richard Fuller is an Australian-born, U.S.-based engineer, entrepreneur, and environmentalist best known for his work in global pollution remediation. He is founder and president of the nonprofit Pure Earth (formerly known as Blacksmith Institute) dedicated to solving pollution problems in low- and middle-income countries, where human health is at risk. Pure Earth focuses on polluted places where toxics cause significant public health risk, initiating projects that solve these exposures thus ensuring healthier lives for local inhabitants.

He is the author of The Brown Agenda, published in 2015.

(source: https://www.pureearth.org/.)

(source: https://www.pureearth.org/.)

In June 2018, Richard was awarded the Order of Australia Medal (OAM) in recognition of his work on polution, conservation and the environment.

In October 2019, Richard received an Advance Award for Social Impact from the Australian government for his 20 years of trailblazing work with Pure Earth and his leadership in tacking the issue as “a toxic pollution fighting hero”.

You can download this episode via the ACAST app here, or find it on any podcast app (Spotify, Apple, Stitcher etc) – just search “ChangeMakers Podcast” and look for the Orange Box!

Join our weekly email list to hear our latest musings, podcasts and training. Click on this button to subscribe:

TRANSCRIPT

Amanda

So, thank you, Richard. It’s really delightful to have you on the line today. And welcome to change makers.

Richard

It’s my pleasure to be here.

Amanda

Awesome So I actually thought just to start off, it would be great for you to give us a sense, give our listeners a sense about what makes you and the work that you do. What makes you a change maker? What makes the work that you do, make change in the world?

Richard

Well, we focus on pollution. For the last 20 years I’ve been building organizations and setting up programs that stop children from dying in low and middle income countries. So now I run an organization called Pure Earth, which you can see, you know, Pure Earth org that operates in around 50 countries around the world. Implementing different projects that take pollution out of people’s impact. So, you know, stopping kids from getting lead in their bodies or bad air pollution, all the rest and doing this in a way where local agencies are learning the skills and are able then to implement them in other places.

Amanda

Well, it sounds pretty important stuff.

Richard

Yeah, it’s, it’s, it’s something that isn’t addressed in most of these countries. So we find that this work is somewhat solitary at least from the international perspective but there is such a need for it when you’re overseas you know, these, these folk are living in some really horrific places.

Amanda

And tell us about that need. Like, what is the scale of the challenge of these forms of toxic pollution?

Richard

You know, it’s difficult to do this in a a quantitative fashion. But there is one toxin that we’re looking at at the moment that looks like we can, we can assess how deep it goes and that’s lead. So by the way, when we look broadly at pollution, look at anything that has a significant health impact, especially for kids. So the range of toxins that worry us are the heavy metals lead, mercury, cadmium, chromium, arsenic pesticides, different kinds of organic compounds that are toxic. And then air pollution, especially PM 25 PM 10. We focus specifically on trying to reduce their levels in places where, where kids are so that we can measure and have a metric for how much they benefited, how much longer life they’ll have as a result of doing this sort of work.

So lead we all remember this when it was in gasoline, at least I do. And we know it, it got out of gasoline and it should no longer be an issue, but we’re seeing it everywhere in low and middle income meta analysis. That’s going to come out soon with UNICEF will show that as many as one third of all children in the world have lead poisoning.

Amanda

Oh my God.

Richard

Yeah. So they have lead at levels in their blood above the WHO safe level. I think that’s extraordinary. And it’s not coming from gasoline lead in gasoline, it’s coming from car batteries and recycling of car batteries. And then sometimes using that lead to glaze your pots to glaze pots or sometimes it’s added to different foods for different reasons as well. It’s everywhere. The more we look, the more we find it.

So if you think a third of all the kids in the world, and look this is, this is still pending final approvals, this piece of research, but it will be done quite soon. That means that a third of all the people in the world, cause they all grow up. They’ve lost between four and five IQ points. On average. They’ve lost probably around a year of life expectancy cause lead causes, cardiovascular disease, and all of those people are somewhere between 30 and 50% more likely to be involved in violent crime. So these are real direct, measurable outcomes from having this much of just one toxin out there in the world. And it’s all in low and middle income countries. There’s very little of this in Australia or the U S.

Amanda

And it used to be, and it was cleared, but it’s not being cleared in those lower middle income countries.

Richard

There’s still a few hotspots leftover. There’s still Port Pirie. South Australia has still got a few lead problems going around. But generally we’ve dealt with them. We’ve had the money and the interest and we’ve dealt the toxic issues in the U S and Australia.

Amanda

It’s extraordinary work that you do. Extraordinary in terms of solving problems like this, like the lead poisoning of our children across the world and other toxic pollution. But also I think that part of it is what’s extraordinary is that you found this problem in the first place, that you were able to discover this problem and then choose to work on it and then scale out a solution on it. And I want to spend a little time for our listeners to understand how you got into this kind of work, how you started to make decisions to eventually work on and build a large organization dedicated to the question of toxic pollution. So if you were to step back and look at your long life, although I’m not suggesting that you’ve it’s that long, but you know, long ish with lots of experience and wisdom. If you look back at the people, the teachers, the things that have driven you, I know early on you particularly had an interest in environmental protection. I’m wondering where did, where did your first passions for these kinds of issues for these, this kind of work come from?

Richard

It started in uni when I was at Melbourne university and some friends, we all decided we’d do some tree planting and started a nonprofit called the Tree Project in Melbourne. And it was an enormous amount of fun and very exciting and we found that we could actually, really do something you can go and see, actually do something physical. So I had a kind of moment after perhaps 10 years after that, after I’d been working and had a successful few years at IBM, where I thought what is it in life that’s worth doing? It’s a short amount of time and what should I do with my life? And I didn’t get all fancy about this. I just sat and thought, what I’d really like to do is I’d like to live in a foreign country and learn a foreign language.

Richard

I thought I wanted to go skiing on the West coast of the U.S and enjoy the Rockies for awhile. And then I thought I wanted to have some way of making a difference at a level that was beyond those people that I met at some kind of a bigger level than that. And then the last thing I thought was I really wanted to see what was happening in the rainforests in Brazil was all Sheeko Mendez that just died and there was a lot of drama around burning rainforest. It’s, it’s obviously it’s back again, but it was pretty busy around that time. So I wrote them down and then I thought to heck with it and sold my house and bought a ticket and went skiing for a while and.

Amanda

Oh Whoa, this is huge. Right. This is not what your average, you know, I’m assuming late 20 year old successful engineer working for a digital company does. Can you explain to us more about that context that saw this moment for you as such a turning point in your life?

Richard

I don’t know if I can, I just, you know, didn’t have family, it was no obligations. It looked like it was a good time to try something. I knew I was safe. If I came back, there’d always be work. I would be able to do stuff regardless. And it looked interesting. It really is. Just a curious curiosity more than anything else. There wasn’t some big epiphany. It was, you know, let it have a shot. Why not? What have I got to lose? That sort of feeling.

Amanda

Was there anyone encouraging you? Was there anyone in your life who thought this was a good idea or who mentored you who encouraged you in this.

Richard

Well, I did have a few, a few mentors, but no one was particularly enthusiastic about this idea of disappearing going into forest. But you know, they weren’t trying to hold me back. They were willing to see how it led and what would happen.

Amanda

Okay. Wow. So tell us what happened. So you got your plane ticket, you did some skiing, but then, what happened?

Richard

Well, I spent then a bit of time in New York and Washington meeting with people who knew what was happening in Brazil. And then I went into the rainforest and I spent about a year there. I’m really deep in the forest, travelling on boats up and down. And I worked with the national government there and the UN environment program, kind of in a loose fashion to become a kind of a consultant, putting together plans for national parks. And it turned out that’s really what they needed. They really needed just someone to do the legwork of saying this is a good area to declare a park. You know, with crown land that people could go in and deforest and then own. But if it’s declared a park, then it would be halted. It would be stopped. So I, I put a ring of parks together around an area that’s being deforested. They’re still there.

They’ve held and you know, with travel I met the then President, President José Sarney for breakfast one morning. It was all quite a surreal whole process. And then after a year or so, the local guys and the rainforest to the kind of the local mafia, the guys who are running their cattle farms and things like that, they found out that this young Australian with a UN business card was was doing this work and they they put a gun man after me, so I scarpered out of there and came back to New York as quickly as I could.

Amanda

Oh my God. You were chased out of the Amazon by an assassin.

Richard

Yeah. Yeah. So that was all a bit dramatic.

Amanda

What was the key lesson that you learned from that experience? That very dramatic experience?

Richard

Carry extra underwear. It’s just terrifying. I was just terrified. I’m not a brave person by nature and I thought that this would, a lot of bravery, was really beyond me. But then I ended up back in New York and by this time I was penniless. I spent all of the earnings I’d had from IBM but I really didn’t want to go back to Melbourne. And and so I decided to see what I could do to make a go of it. And then I started doing different businesses. So I’d given up now the philanthropic kind of side of work and now I decided I would keep working on environment, but do it from a business perspective. So I started a company that was selling recycled paper and that slowly worked but not particularly well.

And then I started a company that was providing corporate advice on how to be sustainable for large corporations, especially for recycling programs and for energy efficiency. And that one did well and took off. And I grew it. Now it’s now the largest firm like that in, in the East part of the U.S and it has done well enough for me now to be able to stop being a corporate guy and go back into the nonprofit world. So about 10 years ago, I turned that company over to management. They’re running it better than I was. And I’m now back doing, starting another philanthropic endeavour.

Amanda

Yeah. And so just before we get to to Pure Earth, It’s interesting that you’ve jumped from the not-for-profit to the corporate and the not-for-profit again. Tell me what, because there are lots of insights that come from those transitions. I’m sure are there any that stand out that you’ve had the benefit of learning that, I imagine that many of them, many of our listeners haven’t had, that those transitions jumping between successful corporate and successful, not for profit. Does anything, did anything stand out from your time at working in sustainability with corporations that you’ve took with you into the not for profit world that you think is really key?

Richard

A things that have shown up there when you look at how well corporations deal with sustainability, there is a strong and honest commitment from companies to do as well as they can within their own field of operations. And you know, I really liked and still do a lot of the people who are trying to make as minimal a footprint as possible within the confines of what their business is supposed to be doing. So there is, there is an intent to do well. They’re often, it’s easier to run a business and make money than it is to run a nonprofit. It’s, I would say it’s about five times harder to develop a nonprofit and make it successful and everyone knows to start a business. You know, your chances of being successful are pretty slim. It’s usually only about 20% of businesses that succeed after the first two years.

So nonprofits are much harder. So the entrepreneurs who are capable of starting nonprofits, they’re very hardy people. They’re very capable of handling rejection and when they succeed, they’re there. They’re really going to be terrific people to be around. But I think what I liked about my path was I never required that the nonprofit, Pure Earth be responsible for supporting my family and my kids’ education. And the rest of it, I had enough from other sources by that point that I didn’t have to be concerned about that. And that made a huge difference to me being able to drive the organization forward.

Amanda

Because resources, particularly in the early years of a not for profit are everything, yeah? The money and the resources to make it happen and where they come from.

Richard

Yeah. Many years it’s impossible. It’s very, very difficult. Raising money is terribly competitive. Yeah.

Amanda

So was there, do you remember the moment where you decided that you were going to step away from, from the sustainability work and jump into the establishment of what became Pure Earth? Was there just like this electrifying moment in Melbourne where you decided that you were going to do something madcap, ski then go learn another language? Was there a moment similarly with the decision to set up Pure Earth, to focus on environmental intervention, to look particularly at toxic pollution?

Richard

It was the boredom of getting my golf game under 10 handicap. And I was trying really hard and playing twice a week and a member of one of those fancy golf clubs and a nice house on the lake and it was like, this sucks, this is not fun. I don’t want to pursue this any further. So it was a, okay, so what, what’s the need at that point, the question was what’s the need? What could I do in the 40 or plus years that have left me that would be, that would be interesting and useful and productive. So when I chose that, what I did then was I brought a lot of people who I knew had a global vision about them. And we had a couple of weekends of drinking a lot of wine, but really talking about where were the needs in the world.

If you’re thinking about the global environment, where were the gaps, where were the things not addressed? And we looked at breaking the world into the rich and the poor and then breaking it into Brown, blue and green. So green biodiversity, blue oceans, Brown pollution. We put another one in with climate as well, and then looked to see where there were efforts and whether they were being adequate to have any chance of being successful in all of those different categories. And the one thing that just jumped out every time we went through this was no one was dealing with pollution, toxics in the poorer countries. It was just not there. It wasn’t on anyone’s radar. None of the large bilateral agencies, not

AusAID not USAID, not the European Commission. No one was doing anything about pollution and its impact. And this is before plastics. You know, plastics is great but it’s not toxic, but it is pollution. So I love it. And so that was where I decided that we should try and do something. So I put the original seed capital into it and convinced a few friends and built a board from a few of my neighbors and got a few $50,000 grants and then a hundred thousand grant and hired a couple of good people and then finally got the European Commission to give us a half million dollar grant and and then started off from there.

Amanda

Wow. What you did. That’s really interesting. And there’s a few people that I’ve interviewed who’ve come at their work, at this work similar to yours from bringing interesting people together to have conversations on the weekend to really nut this out like setting up their own war room or kitchen cabinet to solve problems. It’s interesting how that I think is a really important strategy about how people make change. But what strikes me about it also is that it’s a real head approach to a problem. I’m wondering if there was also any personal experiences that you had had with the question of toxics or whether you then after making this realization went to places that had experienced of toxics, whether you, I guess, whether you had a heart, a heart pull to this issue as well.

Richard

That’s a nice question to ask. One of my best friends in Australia is Peter Hosking and he was also working with me in New York at this time. We went and we visited four different countries and spent a couple of weeks in each trying to understand what was happening and where were the gaps in our countries with dealing with pollution. This was now very broad pollution, looking at sanitation, looking at whether there were NGOs who were trying to do something, whether there are regulations or laws in place, what was happening with toxics and, and health issues. Kind of like trying to get a grasp, a handle on, on how each of these four countries with Cambodia, Thailand Tanzania and Zambia, these four, and wanted to get a sense of where were the gaps, what needed to happen, what could we do?

And we had also small grants to be able to give out, to help different countries try on doing different things to see what would work. So, and doing that, we went out into some really horrible shit hole parts of the world, you know, not anywhere that we’re used to go as tourists and going down into the places where industries set up and there are just, you know, tens of thousands of people and kids living around just horrible dumps piles and living off the scraps of really badly run businesses. And it’s very unpleasant to be there. It’s, it’s very, very unnerving. And you don’t really go there without, feeling ill yourself and then feeling that you’ve got to do something about it. So anyway, so we having done that then that work as we slowly kind of did these assessments more and more, we’d get to how thick people were and how the health issue drives this so significantly. And that’s what, that’s how it kind of turned into the shape of the organization right now.

Amanda

Yeah. Wow. And so tell us what, what does Pure Earth do?

Richard

So we go into very toxic neighborhoods, sometimes whole cities and we work out a solution that will mitigate those toxins and get them out of the place. It usually starts with stopping whoever it is that’s producing them from producing them. One of the lesser known realities of this is it’s never a big fortune 500 company who is there. Very often the toxins are coming are there, because small artisinal activities, people just trying to make a living, they’re doing it in very toxic, toxic way. So it’s often helping these communities to handle their own industriousness in a way that doesn’t kill their children. And so, so there’s a lot of training work that will go on. We’ll bring in technical experts that know how to help change those industries and then we’ll help them to clean up the mess that’s left behind. Once we no longer can see that there’s any more exposures going on, we’ll help to clean up the mess that’s behind and measure, you know, before and after with kids and health assessments and a lot of universities are involved with us. And then move on to the next one. We’ve done about 110 of these.

Amanda

Yeah, it’s extraordinary. One of the questions I want to ask you about is, is actually about this process, about, about how you make change. Cause what I’m hearing in your description is that there is the building of a partnership between Pure Earth and a community about, around pollution and, and it’s an in its of the industries that are working in those communities and there’s a whole process of learning and education and um and work. And I wanted to, Oh, I guess I want you to talk about a little bit more from my work as an organizer. I’m really aware that there are lots of different ways in which that kind of change can occur. You know, you can, you can make change for communities. You can make change with communities and there even though they both achieve outcomes, like they could both remove pollution or you could, you know, whatever social change issue that you’re wanting to achieve, how you do it um, is critical for determining how long the change lasts. Can you tell us a little bit about how Pure Earth works with the communities?

Richard

Yeah. Our experience here is that the less the requirement that the organization is involved in the process, the better it is. So the more we can, they’re just providing support and encouragement and assistance and education and let local stakeholders take on the challenge and do the work the much better it is. So, you know, look, I think this is true, even in the process of any sort of change at any sort of level, what you have to do is you have to build a network of people around you who believe in the same mission and can see ways where they can begin be productive within that mission. And that’s when you start to see change happen at a kind of more systemic level. So, you know, the practically, the way that shows up for us is when we go into a community, we’re only there having been invited by the local governments and mayors and CSO’s and the rest. And we’ll form a stakeholders group is the first part, and have them sit down and bring a technical team who can say, here’s the solution. Here is how this would work. And you know, how can you do this work? How can we help you to do this work and then follow that process through with them over the next period of time. So it has to be done in that kind of collaborative, networked way.

Amanda

Yeah, absolutely. Certainly. That’s utterly true of my experience because otherwise things fall apart after you leave if they’re dependent on you when they start. And we don’t want that for them to, if there’s change to be able to last. I’m wondering if I could ask you to think about the most memorable intervention that you’ve been a part of. I mean, Pure Earth has been around for a long time. You’ve got dozens and dozens that will, 110 stories as you described them. Can you think of a memorable intervention and just paint a picture of us for us. Paint a picture for us about, you know, what it was like when you started and how it shifted.

Richard

I can give you a couple of these, but a lot of these are in, in my book.

The Brown agenda and it’s on Amazon and you can get an audio book as well as, digitally downloaded. So, so there’s quite a lot of good stories in that.

So I’ll tell you two stories. One, that’s one that’s in the book, the beginning of it, which is kind of what’s kind of crazy and dramatic. So there’s a place in Eastern Ukraine called Horlivfka. It’s now controlled by the Russians. Part of Ukraine, that’s been taken over by Putin. But this place had an abandoned factory there that was making TNT for the explosives industry. This place had a factory that had been abandoned. The Soviets used to make TNT there, but it had been shut down about 10 years earlier. And I had a team of people from the former Soviet Union though that would, we were teaching how to do site assessments, how to go out and discover something was acutely toxic and would be killing kids or not. And there’s a methodology to do that that we’ve put together and we run workshops all over the place. And I was running one of those early workshops and it was freezing cold and we’re on the edge of a cliff looking down into this old abandoned mine where they are mining mercury. So we were looking for evidence of still toxic mercury around this place.

So we’re looking for mercury, but there’s two black SUV pulled up and this Russian guy yelled at, yelled out the window, come here in Russian. So our Russian guy went across and started talking and then he came back to the group and said, Richard, you must go with them. And I said, how could that be what I go? He said, you have to, they’re the government. You have to. So we both went and the, this guy, you know, big Russian, furry hat round, ruddy face looks at me and says, get in.

And I’m like, you know, I’ve just thought this, is this the same as Brazil. And I being finally being caught up for my sins here. So I got in the car and my Russian guy and him and two other people started talking very loud, very fast in Russian and I couldn’t follow it. And finally my translator Vladimir turned to me and he said, don’t worry Rich. It’s fine. They don’t want to do anything to us. They need our help. And he drove us to this factory that had been abandoned, that was making TNT

So, so we, we went into this factory and went inside and the chap IRA may, who was with the U S army technical team he looked at these bags of stuff that was spilling everywhere and he just said, we have to get out of here now. And the factory was, had been making mano nitrile chloro Ben’s in his MNC B material. And it would then get turned into TNT or it could also get turned into making nerve gas. It was, you know, WW2 factory. And when the, when the supplies, when TNT was no longer being requested by the Soviet Union, this factory in the Ukraine just kept making the precursor and they made hundreds of tons of it when they didn’t have any place to store it. And it’s toxic enough that four grams will kill a human, an adult. So there was just tons and tons of this toxic stuff blowing all through the factory and ready to, you know, destroy the town if it ever kind of would blow up into the air.

And then it float down into the town of 200,000 people and kill half of them within the next, you know, 20 minutes or so. It was extremely toxic, you know, potential here. So we backed out and I put together a team of experts, including folks from Dow chemical and, companies that are supposed to be the evil empire that actually showed up and did some really great stuff. And brought in a bunch of technical experts and hired a lot of former Russian Soviet soldiers, trained them in proper protective gear. And we packaged up all this material and shipped it to a incinerator, a high tech incinerator in Germany where it was destroyed for free by one of the big multinationals as well. And the place became safe. But that was a pretty crazy thing. That was a crazy place.

Amanda

Yeah. And the story, that’s super crazy. Don’t get me wrong. That is definitely up here on a crazy list. But I also, what I hear in the stories, the how you were able to solve that crisis using a whole bunch of unusual alliances, bringing in people who, if you had been dogmatic or not pragmatic, you might’ve not thought of them as partners, but you were being pragmatic, you were in a crisis and you’re able to draw a whole bunch of people in to help with the solution.

Richard

Yeah. I reckon that’s critical. You know, there’s no need to be aligned with any particular, you know, political ideologies or any, anything in those matters. Just about how do you go about fixing it. This is the engineer’s mentality. You know, the geeks do inherit the earth. These are the people that know how to make things happen and, and fix things and and you know, more than merrier.

Amanda

I love it. I love it. The engineer’s mentalities are pragmatic mentality. We need more engineers in social change.

Richard

Well, you need engineers everywhere. You know, it’s engineers that have created Microsoft, that help Gates to go out and save you know, tens of millions of people from, with vaccines and all the rest of it. It’s engineers are the guys who forget about all the drama and Sturm and Drang and just get things done.

Amanda

Yup. Well, I’m so glad that you as an engineer have become a changemaker and abandoned your golfing career in order to be able to work with the likes of those wanting to make the world a better place. My last question for you is just to reflect on the lessons that you’ve learnt in your time across so many different planes in the profit and not for profit world. From your planting tree organization from when you were in university onwards. Are there any key lessons that stick with you about what it takes to make powerful change?

Richard

I would think that persistence really is really important. The majority of endeavors, the majority of proposals that are written, the majority of attempts to create, you know, a workable coalition, they fail. And so you just have to kind of be stubborn and pigheaded about it and keep trying. And it does get there. It just, you just, you know, trying once and then having it fail is fantastic cause that means you’re one less until it works. That and then the other thing that I know works well is just getting some terrific likeminded people who can see and help and develop the vision, help and develop, you know, what you want to see the world look like. And having a great group of people who, who are turned on by that is, is it really makes life just so bearable. It’s really great.

Amanda

The power of a great team.

Richard

Super, super, super. I love, I love the people that I work with. And, and they’re doing 99% of the work. I, just can’t imagine any kind of change possible without all these fantastic people with who are there.

Amanda

It’s been so spectacular to talk with you and congratulations as well on your, your Advance Award for impact on a social impact. I mean, what an extraordinary recognition for lots of extraordinary work that you’ve done. And it’s been so delightful that we’ve been able to provide a space where you could share both your life story and your life lessons with the ChangeMaker audience. So thank you so much for your time.

Richard

Amanda. It’s been lovely chatting with you.

Join our weekly email list to hear our latest musings, podcasts and training. Click on this button to subscribe: