How decades of fast food worker organising lead to “The Fight for 15”

By Keith Kelleher, Founder and Former President of SEIU (Service Employees International Union) Healthcare Illinois, Indiana, Missouri and Kansas.

The First Spark

“…On Thursday, May 28, 1981, at or about 11:30 am, a number of off-duty employees, in the company of union organizer, Keith Kelleher,…entered Restaurant 768, …moved toward the back of the kitchen in the direction of the manager’s office. Kelleher asked employees…to join them, and a few, including discriminatee Cynthia Diane Williams …did so.

“…On Thursday, May 28, 1981, at or about 11:30 am, a number of off-duty employees, in the company of union organizer, Keith Kelleher,…entered Restaurant 768, …moved toward the back of the kitchen in the direction of the manager’s office. Kelleher asked employees…to join them, and a few, including discriminatee Cynthia Diane Williams …did so.

Williams and… employee Luther Wyatt came to the front of the crowd…and entered the office. Williams told Amato, that the United Labor Unions represented the employees, exhibited to Amato a sheet of paper containing a proposed union recognition agreement, and asked her to sign it. …Amato… refused, saying she had no authority to sign. At this point, the crowd took up the chant, “Sign it, Peggy! Sign It!” and continued this chant for about 20 minutes…”

– Extracted from National Labor Relations Board

So began one of the most exciting actions I’d been a part of since I started fast food worker organizing in Detroit 1981. I had been hired on March, 1st, 1980, by the then-fledgling Detroit local 222 (the “triple deuce!”) of the United Labor Unions (ULU), an independent union, unaffiliated with any larger labor federation but which itself had been founded by the national community organizing group ACORN (Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now).

In 1980, US Steel and GM were still major American employers, but McDonald’s and other fast food giants were gaining fast. Oil shocks and economic shocks were throwing millions out of stable union work, but one industry gaining fast was non-union fast food.

Then in the early 1980s an unheard of plan began: workers employed by McDonald’s and Burger King in Detroit started organizing for better wages and benefits.

I was a young organizer working alongside this first generation of fast-food leaders at the Greyhound Burger King inside the bus station in downtown Detroit. After three years, workers won a union contract, one of the first union contracts in fast food settled in the United States. But even with that victory, it was clear that management would do anything to fight off workers’ attempts to organize, and they had the money and resources that workers did not.

I’d been doing it tough: after badly losing my first union organizing election at a different Burger King store, miles away, on the southwest side of Detroit we made attempts at organizing others.

We all got an early lesson in the kind of dirty tactics that the fast food bosses would put into action to

stop us organising a union. Some of the workers at my first store called us back one year later and we reorganized around issues of management harassment and mobilized around the first “recognition action” described at the beginning of this article. The Burger King corporation, knowing they would lose the rerun election because of our overwhelming strength in the newly organized unit; SOLD THE STORE to a supposed “franchisee” who just days before had been a human resources director for corporate Burger King! Even we, who by then were hardened veterans of vicious fastfood organizing drives, were stunned that the Labor Board ruled in this huge corporation’s favor and gave it their blessing.

Our vision was ambitious but simple: organize the low-wage fastfood industry, as well as other low wage industries across the United States and organize low-wage workers everywhere to reap the higher wages, benefits, and working conditions that unionization can bring.

We wanted to “build the movement,” to achieve even more radical change throughout the country: through changing labor laws, reigning in the power of public utilities and banks, fighting discriminatory laws in housing, and change the two-party game of electoral politics. We were young and we really wanted to change the world!

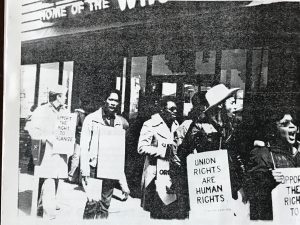

Big visions were nothing new to the ULU and ACORN organizers – many of the older organizers who had hired and trained me were veterans of the anti-war, civil rights, welfare rights, womens’ and community organizing movements of the 60’s and 70’s. Skilled organizers committed to organizing low and moderate income working families to build community power, through direct action like recognition actions, sit-ins, marches, demonstrations, and whatever else worked. ACORN had grown from an idea formed by veteran welfare rights organizers in 1970, to offices in over 20 US states by 1980.

ULU wanted to replicate that growth, but grow faster, by organizing fastfood and other low-wage workers with a new labor organizing model based on community organizing. We would fuse the best of labor, community and political organizing techniques into a hybrid to organize these fast-growing service sector jobs.

By the time, I came on board, ULU was already two years old and had graduated from experiments organizing the unemployed, and household workers, and others and was reaching for something bigger. In two years, they already had four locals in Detroit, Boston, New Orleans, and Philadelphia; and one of the first labor organizing retreats set a goal of organizing 50,000 new workers within the first year!

We were learning on the run and this small effort taught us how the fast-food giants think and that they will stop at NOTHING – even selling a store – to keep wages low, jobs part-time, and zero benefits. Over 30 years later the tactics of McDonald’s have not changed.

I eventually moved to Chicago in 1983 and founded ULU Local 880, which would soon become SEIU Local 880; and eventually organized over 70,000 homecare and childcare providers into Local 880. I also headed up the SEIU Homecare Organizing Task Force from 1996-1998, which eventually led to SEIU organizing over 600,000 homecare workers, as well as organizing another 100,000 childcare providers – one of the largest organizing drives in modern US labor history.

But in 2012, a new generation of organizers and workers took a crack at the industry that had got me into the union movement in the first place– they again wanted to organize fastfood.

I was asked to put together a memo on fastfood organising “best practices” and strategy, gleaned from our early years of organizing fastfood workers in Detroit in the early 80’s – in the hands of the skilled organizers of NY Communitites for Change and Action Now in Chicago, this memo helped guide some of the early thinking and strategy in this new generation of organizers and leaders.

In November 2012 this new generation of courageous fast-food workers called for $15 an hour in Chicago on the Magnificent Mile and then in a one day strike in New York City. Like the earlier effort I was involved in, the workers received critical support from the community— many of them veteran ACORN organizers – this time from SEIU, New York Communities for Change, Chicago’s Action Now and Leadership for the Common Good.

With workers taking the lead and unions and community groups showing support, a movement rose that has expanded to more than 300 cities and tens of thousands of workers. Low wage workers are now organising nationwide for a new minimum wage – $15. Across the country, 20 million workers have won big raises since those brave workers in Chicago and New York City started their Fight for $15 in 2012. The workers in the Fight for $15 are learning the same lesson we learned over 35 years ago—when we fight, we win!

Join our weekly email list to hear our latest musings, podcasts and training. Click on this button to subscribe: