If all organising is disorganising and reorganising – let’s reorganise how we think about mental illness

By Amanda Tattersall. This speech was prepared for the Brain Difference Workshop held by the Sydney Alliance on 3 November 2021.

I have walked a life living two identities. I am on the surface, ‘normal’ Amanda. I work, connect, and strive in the world just like you. At my core, I have lived a life yearning for change. I am an organiser.

I discovered organising in the wake of the social movements that rose and fell around the war in Iraq back in 2003. I joined a massive coalition in Sydney that held enormous demonstrations, but despite our passion, we didn’t succeed. It was a turning point for me. I embarked on a quest to find different ways to make change. In 2004 I enrolled in a PhD and travelled to North America where I soon found organising. I met people like Mike Gecan and Joe Chrastil from the Industrial Areas Foundation and did their five-day training. But change is hard and I wrestled with organising initially. I didn’t love the IAF’s idea of compromise and I found the practice of relational meetings troublingly difficult. But as I finished my PhD and contemplated my return to Australia, my resistance reorganised. The rest is history – the Sydney Alliance began and still lives decades later. Community organising grows across Australia.

But I also have a secret identity. It’s usually invisible. But if I trust you, I might share a little detail. It’s not something I am in control of and occasionally it surges out of me. It is ‘awe-some’ in the truest sense of the word – it’s stunning. It shocks. It can, at times, disgust.

My secret identity makes me different. It’s because my brain is different. I have a serious mental illness – bipolar disorder – 1, which means that I live with mania and depression, and have experienced psychosis.

It’s confronting to learn that the life that you hold together is not how others live. I was always aware of the obvious differences, like being hospitalised in a psychiatric ward for two months when I was 19 or losing my job because of my mental illness when I was 38.

But it’s the little differences that stand out to me. Like how my brain and body work in tune with the seasons. Every winter I have to resist my brain’s call to depressively retreat. Then, in Spring, along with the scent of the first jasmine, my skin and mind electrify. I am forced to stage a siege encircling my brain, containing a volcanic energy that no longer needs sleep and is reverberating with ideas. They are often very good ideas. I am forced to extinguish them in order to function.

And this is my medicated brain, that attends weekly therapy, engages in daily exercise, and partakes in every clinical and social routine that medical evidence says will help. This is how I keep going. To do what many of you do without thinking.

Many of you. But not all of you. Plenty of you know what I am describing. Twenty percent of us experience a form of mental illness in our lives.

Mental illness shows up everywhere, including in our not-for-profit organisations.

Historically, civil society was the first to step forward and engage with the mentally ill. Yet, like it was for others who were different – the health system and our community organisations didn’t know what to do. Mistakes were made. Even up until the 1980s in Australia, people like me were locked up and taken away from their families permanently.

But things changed. Mental health consumers pushed for the dismantling of most long-term psychiatric hospitals. We were released, but there was a catch.

We had new masters – the world of health care. Doctors, psychologists and well meaning clinical support groups like Beyond Blue and SANE.

It was better. No question. With medical support I can manage my life. My brain difference is a gift, but it isn’t alway pretty. I need help and I can now find it.

But when my brain is only seen through a healthcare lens – I remain a patient. A healthcare lens defines my mental illness – my brain difference – as a private concern.

As an organiser I know the power that comes from defining something as private or public. Take a housing crisis. When you see your personal inability to pay the rent as private, you blame yourself. But when you can see that your situation is caused by greater forces in the public world – like a lack of housing supply – everything changes. When the problem is defined as public you aren’t left blaming yourself – you can see how you can change it. Instead of blame, you feel anger, an anger sourced in the love that has been denied to you and others like you. Seeing something as public or private makes all the difference in the world.

Feminists knew this a long time ago. The slogan the ‘personal is political’ insists that the criminal justice system should not deny women safety from domestic violence just because the violence occurs in the private home.

Seeing mental health as only a private healthcare issue is a problem.

Seeing mental health as a private problem means that when I get sick I blame myself that I have a failed brain, rather than questioning how the world around me might have contributed to my illness. It means that when I stick my head up and talk about my mental illness I am attacked by people who say that I am crazy or unstable. It means that we live in a world where people are too scared to be vulnerable and talk about their anxiety or their depression – frightened that speaking up might lead them to be punished at work or ghosted by friends. Defining mental illness as a private problem can never end the stigma around mental illness.

Of course I and others with a mental illness have a private role to play in being healthy and accessing healthcare, but that argument feels like gaslighting these days. The very health system, as limited as it is, is in deep public crisis. Doctors are impossibly hard to access. When I had a psychosis in 2015 it took a month before I could see a new psychiatrist. And when you turn up, doctors are extremely expensive – my weekly doctor visit cost $420 before Medicare.

Seeing mental illness – which is now raging in unprecedented proportions – as only a private issue will never actually fix the problem. A private lens cannot unwind, question or change the social contexts – the workplaces, the social relationships, the immigration systems, the education systems – that cause people to be sick. But secondly, this private healthcare lens assumes that all we need is to be made normal and the same as everyone else.

If we want to create a thriving society for people like me, we need to reorganise how we think about mental illness. I have had to live with two identities because the whole of me doesn’t fit into how the world wants to see me.

Mental illness needs the support of healthcare professionals, sure. But it can’t be defined by this private relationship. I am different not only when I walk to the doctors office, but when I walk into work, into my union or into my community organisation. All these public systems need to be reorganised if we want people like me to thrive.

My brain is central to my identity, but at the same time I am not making an argument for a rigid or fixed approach to identity. Appropriating how organisers think about ‘self-interest,’ I see identity as something that exists before we are born and is constantly shaped by our experiences. Our identity – my gender, my brain – like our interests, live in our being but are also becoming.

What might we do?

My experience has sparked ideas for reimagining our public space to support brain difference. An obvious one is about flexibility around hours and leave at work. A deeper one for non-profits is owning how the not-for-profit world trades on passion. Civil society’s greatest strength is that we stand with injustice and pain, and we are called to find remedy. Yet this pursuit often comes with its own pain – justice cannot always be found. Social change is rarely a Hollywood story. But it’s more than this. Our organisations – your organisations – often call on our people to act and to work based on their commitment. We draw on people’s passion to try harder, to work longer. Sometimes this is a righteous call. And sometimes it leads to burnout.

But we need more than a brainstorm here.

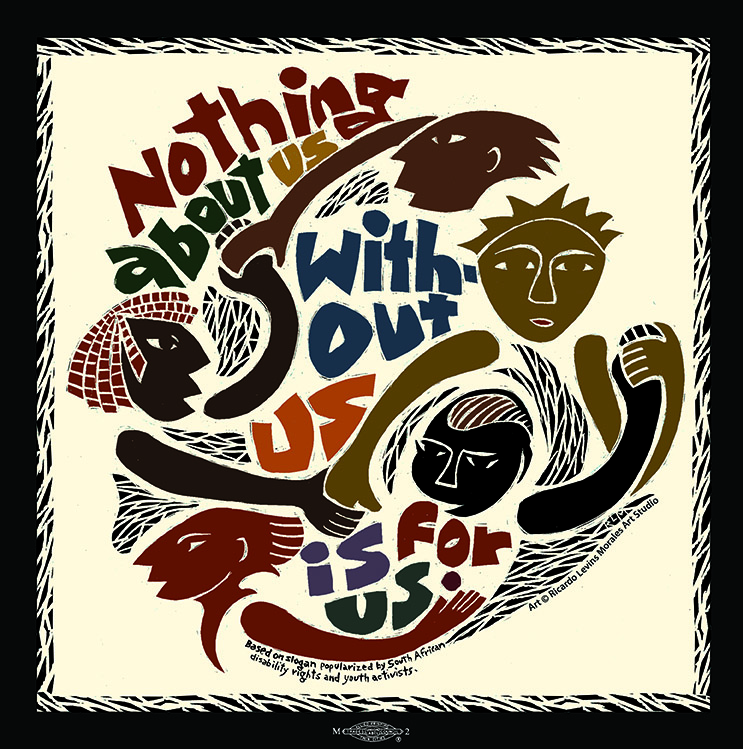

Over 50 years ago the disability movement built a slogan that is an operating principle for change. ‘Nothing about us without us.’ It reminds me of the iron rule of organising – ‘don’t do for others what they can do for themselves.’ The disability movement argues that those who have a lived experience of a disability or mental illness need to be at the table playing a leadership role in making change in the same way that organisers create space for everyone to find leadership.

At the moment, the organised mental illness community is weak. There are very few organisations with only a handful of people with lived experience exercising any power. The strongest advocacy is led by doctors. People like me are hard to see.

How can this change?

When I started the Sydney Alliance I believed that we could change the debate on the big issues in Sydney by bringing together the most powerful civic organisations. Inside of those organisations every issue under the sun was felt – from housing, to migration, to education.

Today – in the wake of the pandemic – If mental illness is an epidemic everywhere, it is an epidemic in your organisations. You know this. You know the trauma that people are experiencing personally.

What I am arguing is that personal support is not enough. More telehealth or cheaper doctors or a mental health crisis plan is not enough. What is needed is for people to have the space so they can come together, talk together, imagine together and identify solutions to what they are going through.

Mental illness doesn’t need more niche specialist groups. It needs people with a mental illness defining the solutions that would make their lives better everywhere. And to do this – it needs mainstream organisations like yours to take this on.

Imagine a day where you created space that allowed people with brain differences to come together and talk about how their lives were going and what could make a difference. You would be part of creating a space that said – the pain you feel is not your fault, but it sits in public life. And together – we can do something about it.

ChangeMakers is a Podcast that began in 2017 and has years of stories and interviews with people making change around the world. Check out our interviews – ChangeMaker Chats, and our Stories over the years under the episode tab.

Join our weekly email list to hear our latest musings, podcasts and training. Click on this button to subscribe:

_

Comments

Stay Up to Date!