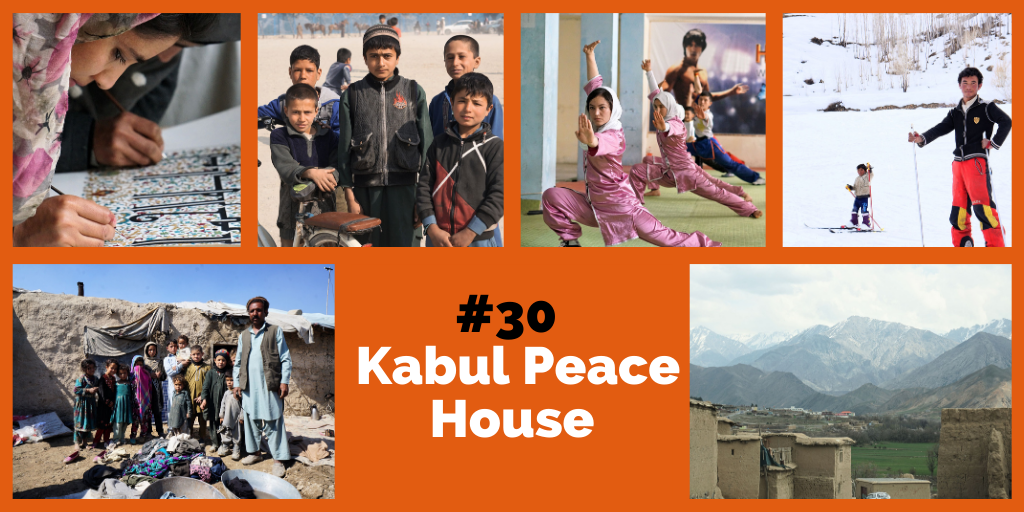

#30 Kabul Peace House

During the 2000s, in the mountains of central Afghanistan, a remarkable but unlikely peace movement began. How did they even define peace in a place beset by war, and how did they organise themselves to work towards this audacious goal? Listen to the episode on iTunes, Stitcher, Spotify or most podcast apps.

Short video clip about Afghanistan and book:

Hardie Grant:

Reviews:

Donations:

https://www.erc.org.au/afghan_project

Join our weekly email list to hear our latest musings, podcasts and training. Click on this button to subscribe:

Episode Transcript

HOST

Where in the world would you expect to find a committed movement striving for a green, equal and on non-violent world?

INSAAN

The … volunteers … wish to build a critical mass of non-violent relationships by building a green, equal and non-violent world without war.

HOST

That was Insaan, the mentor of a community of more than 50 peace activists located in Kabul in Afghanistan.

This is a story about building peace in a country that has been at war for more than four decades.

INSAAN

They’ve never lived peace to know exactly what they’re talking about or what they want, except it’s there as a want. It’s one of the biggest things that the community could take on… But it’s the only one because the fighting won’t stop until someone says enough.

HOST

Today on Changemakers, our story is about Insaan and a community of young Afghans – both male and female – who work together across ethnic and sectarian divides to build peace in Afghanistan. In Afghanistan calling for peace can get you killed. So how do you start to build peace in a place that has suffered endless war? How do you mend decades of distrust and violence that has torn a country apart? How do you restore hope in the hopeless?

Let’s go.

HOST

I’m Amanda Tattersall, welcome to Changemakers, the podcast telling stories about people changing the world.

We are supported by the Sydney Policy Lab at the University of Sydney. They break down barriers between researchers, policy makers and community campaigners so we can build change together. Check them out at sydney.edu.au\sydney–policy-lab.

The interviews in today’s episode were undertaken in 2016 and 2017 in Afghanistan by our reporter Mark Isaacs, who also wrote this episode. These stories also appear in his book, The Kabul Peace House. In reporting this story we have changed the names and identifying features of the community and its members to protect their identities and respect their anonymity. The identity of our main character – Insaan – is kept ambiguous at times. In order to anonymise him we have employed a voice actor to read his exact words, and have omitted certain identifying details of his life.

We will meet him soon. But first we need to zoom out – to better understand Afghanistan.

HOST

Afghanistan has been at war since 1979, when the Soviet Union invaded and occupied the nation.

Musa Mohammadi is the former executive director of the Afghan Independent Human Rights Commission.

MUSA MOHAMMADI

The social fabric was destroyed, the culture was destroyed, the tradition, the infrastructure, anything, the academies, our social respect, all those things that we had, it’s gone now.

HOST

Nowadays, few Afghans remember what it is like to live without war. Abdul’s family were Pashtuns from Paktia province who fled the Soviet brutality and became refugees in Pakistan.

ABDUL

The Soviets made the women watch as they tied their husbands to the tanks and dragged them on the ground until they were killed.

It was just a matter of fate or chance or bad luck where the bombs were dropped and who would be killed.

The men lost all hope in life, They took up weapons in the name of jihad, the holy war.

HOST

A national resistance movement formed against the Soviet forces. People divided into groups of fighters called Mujahedin, which frequently is referred to as “Soldiers of God”. Soon, every part of the country, every valley, every district, was ruled by a Mujahedin commander – a warlord – and his militia.

MAYA

Herat was one of the cities, big demonstration, Black Friday, people coming from the villages screaming against the regime in the town and then the government people they shoot people. So many people killed. The government had their military base outside of the town and they are attacking with missiles..

HOST

By the time the Red Army withdrew from the country in 1989, 1.5 million Afghans were dead. The militias who opposed the Soviet Union turned on one another and engaged in civil war. Out of this turmoil emerged the Taliban, who ruled the country until 2001, enforcing a controversial interpretation of Sharia that was lacking in historical perspective or tradition. They targeted anyone opposed to them, particularly the Hazara ethnicity, and they severely oppressed women. Hojar’s family lived in a Hazara-majority area of Afghanistan.

HOJAR

When I was 7, going on 8, the security situation became intolerable because the Taliban had come and we felt that we needed a way out of the place because things were getting too uncertain. We would sleep at night with our shoes on in case we needed to escape.

HOST

One evening the fighting became so bad, the family fled the village. But the Taliban soldiers chased them and caught them.

HOJAR

After they took the men, they told the women, now you can go home. We were so frightened we didn’t protest. Shortly after that, from behind them we heard the sound of gunfire. They had executed the men.

HOST

One of the executed men was Hojar’s father.

HOST

Then September 11 happened. One month later, Osama bin Laden, filmed from a cave of an Afghan mountainside, claimed responsibility.

OSAMA BIN LADEN

[0:45] What America is tasting today is something insignificant compared to what we have tasted for scores of years. Our nation [the Islamic world] has been tasting this humiliation and this degradation for more than 80 years. Its sons are killed, its blood is shed, its sanctuaries are attacked, and no one hears, and no one heeds.

HOST

After 9/11, the Taliban refused to cooperate with the US and their request to extradite bin Laden. War was imminent. The United States – the world’s biggest superpower at the time – wanted revenge.

GEORGE W. BUSH

[0:47] Our enemy is a radical network of terrorists and every government that supports them.

[3:30] We will direct every resource at our command, … to the defeat of the global terror network. [3:51] [21]

HOST

In October 2001, United States and British forces invaded Afghanistan in alliance with a coalition of Afghan forces. Within three months, they had captured Kandahar, and severely weakened the Taliban regime.

INSAAN’S STORY

HOST

At that time, Insaan was 32, working as a local doctor. One day in 2002 in the wake of the US invasion, he had a chance encounter.

INSAAN

One day I was in a clinic and a patient came in.

He had been doing some humanitarian … work at the border of Pakistan and Afghanistan in this city called Quetta.

They really needed medical people there. It was a horrendous refugee situation.

HOST

Insaan always wanted to do more to serve humanity. This was his chance.

The patient connected Insaan with an organisation working with refugees. Isaan sold his share in his medical practice … and moved to Quetta, Pakistan where 1.2 million Afghan refugees had gathered.

INSAAN

A trash collecting Afghan Pashtun boy, had lost both his father and mother in Kandahar in the southern part of Afghanistan and he fled from the bombings and then became a refugee in Quetta… He was one of my first face-to-face encounters.

HOST

That young boy was Amaan. Insaan wanted to help Amaan but what could he do? There was no simple solution for any of the million refugees displaced in Pakistan.

INSAAN

That story of his life made me think … of the many problems that all the Afghan refugees had to face and that changed me.

I finished medical school but I didn’t think hard enough about root ways of resolving very real problems which afflict large numbers of people.

HOST

He needed to be more than the ambulance at the bottom of the cliff.

INSAAN

That has brought me to this point then, in thinking deeply about why Afghans need to live this way … and what should we as human beings do along with them.

HOST

This idea remained with Insaan as he worked on the border, and then into his next posting in a village in the mountains of central Afghanistan.

INSAAN

There are maybe a hundred and fifty families in that village.

The houses are made of mud. And around the houses is wheat and potatoes and poplar trees.

I woke up to heaven every morning.

HOST

In these remote villages Isaan began to find ways to put into practice the insight he had in Quetta. He started to work on preventative health.

INSAAN

That first public education campaign was on water because diarrhea and the lack of clean water is one of the major killers of Afghan children and causes of mortality in Afghanistan.

That work and living in the village exposed me to needs other than medical needs.

There was a need for safety. A need to be healthy inside. A need to work through feelings of anger and revenge. A need to learn. A need to know how to work with the land.

HOST

But while he found lots of particular causes – health, water then education – something deeper lay at the centre of all the pain he encountered.

INSAAN

Again and again in my work I would encounter these same root problems… You can’t address any family’s problem without having to address the problem of war… Some of them would even say we can handle weeks of hunger, but we just cannot have another family member killed. We will break.

I began to see that it was important for me in order to love the people here, to be able to address the issue of death, of war, of why the world has become like this.

HOST

What could he possibly do?

INSAAN

My world was turning upside down and I thought, okay maybe let’s start off with organizing a peace workshop.

HOST

A peace workshop.

The local university approved Insaan’s idea and fifty students agreed to meet on a weekly basis over a three-month period. Insaan didn’t have a plan, he just wanted to begin a discussion.

At the end of the three months, Insaan brought the community together for a final reflection.

INSAAN

The conclusion of the workshop by the majority of the participants was that peace in Afghanistan is not possible.

HOST

Insaan was undeterred. He had a suggestion.

INSAAN

It was quite clear to me that one contributing reason to why … human beings think they’re better than another human being is the ethnic issue.

I wanted to explore the possibility of undergraduates from different ethnic groups living together for one semester.

HOST

People couldn’t believe in peace because they couldn’t see people overcoming distrust and hatred for different ethnic groups. So Insaan theorised that if they could create a microcosm of a peaceful multi-ethnic community in their town, they could act as an example to the rest of Afghanistan. His school could pre-figure what Afghanistan could be.

One of the biggest sources of conflict in Afghanistan was between ethnic groups and Muslim sects. At that time, the hostilities and divisions caused by war meant the Tajiks and the Hazaras in the region were not on friendly terms. Hafizullah grew up in this hostile environment.

HAFIZULLAH

It was so bad that when Hazaras and Tajiks met, without even speaking to each other, based solely on their facial expressions, they would start fighting.

I subconsciously felt that Tajiks were my enemies.

HOST

This was going to be hard.

MUSLIMYOR

When I heard about the possibility of the youth not only working together but living together, I thought, “Well, that’s not going to be possible”.

HOST

Muslimyor had good reason to be skeptical. His brother who was a soldier in the Afghan National Army was killed by the Taliban.

MUSLIMYOR

The bullets had gone through his eyes. They also went through his chest and back.

He was young, 23 or 24 years of age, survived by a new born daughter. This is life in Afghanistan.

HOST

Despite all this, at the end of the 3-month workshop, Insaan got his greatest boost yet. He was approached by sixteen male students from seven different ethnic groups who wanted to participate. And so began Insaan’s experiment in peace.

HOST

The experiment immediately drew suspicion. Outsiders couldn’t understand why young people from different ethnic groups and Muslims sects were mixing.

INSAAN

I thought it was a potentially good controversy.

HOST

Insaan had hoped that the multi-ethnic community could have started people questioning their own ethnic prejudices. However, one day, Insaan received an anonymous letter that said: ‘Leave the mountains or we will hurt you.’

INSAAN

I imagined being shot in the back. Or being taken. It was so real because then I thought am I prepared to have my life end there, not even for the cause of peace or social work, but just for, I don’t know what, you know it was probably money.

HOST

At the urging of his employer and friends, Insaan agreed to leave the area temporarily and return to his parents’ home. While he was away his conviction only grew.

INSAAN

I was more and more convinced of the fact that this was something I wanted to do.

This needed to be a struggle. This needed to be my own personal journey and I needed to remain committed to it. Perhaps foolhardy that it could result in me being hurt or killed.

RESUMING THE EXPERIMENTS IN PEACE

HOST

Despite the fears and dangers, Insaan returned. The students from the first live-in trial were determined to carry on with their peace work. Insaan wanted to start a group that conversed with fellow Afghans, discussed basic principles of peace, morality and law. He wanted to place the universal values of peace in the public consciousness.

MUSLIMYOR

When I heard that the youth were working for peace, I liked the idea. That made me want to try.

I had heard radio programs talking about how it was important to bring peace to this country and I was keen to try it out.

HOST

The students and Insaan invited young people to their group and they started to perform actions in the local area to promote peace. They organised a peace trek through the mountains and they arranged a ‘clean and green’ campaign to clean up the local township. This campaign paved the way for their next big idea, the building of a peace park.

PEACE PARK

HOST

They picked a plot of arid land covered in pebbles, stones and boulders, located on the fringes of town and asked the local government for permission to build a peace park. No-one in the local area thought it was possible. One local politician remarked:

INSAAN

You want to turn that into a green space? You need to be a bit more realistic in the things that you do in life.

HOST

They weren’t deterred. They recruited local businesses and government departments and by October 2009, the once arid plot of rock was looking like a fertile oasis. A local politician commended their efforts.

GOVERNOR

Unfortunately, through years of war and conflict, we’ve lost some values. We’ve lost self-sufficiency and self-belief. Everyone waits for a foreign NGO to place a stone or brick before doing anything. Building this peace park is an example … that we can build our own country and not be dependent on others.

HOST

The group was beginning to believe in their work and themselves. They hoped that their example would motivate other Afghans to take responsibility for the future of their country and their communities. On a sign in the park they wrote:

INSAAN

Even a little of our love is stronger than all the wars.

ETHNIC EQUALITY

HOST

After a number of successful community-building projects, Insaan suggested it was time to push themselves outside of their comfort zones.

INSAAN

Our next thought was to reach out to Pashtuns in Kandahar province, the heartland of the Taliban.

HOST

This was hugely controversial. In their region, a Pashtun person was synonymous with the Taliban and many of the local people, including members of the group, had suffered at the hands of Taliban forces.

HORSE

I was afraid of Pashtun people.

Because I had heard that Pashtuns were wild.

My relatives hated the Pashtuns.

They would respond to news of Pashtuns fighting by saying if we catch them we will kill them.

HOST

And I thought coalition building in Australia was hard.

Insaan believed negotiating peace in Afghanistan would be an exercise in trust and compromise. In order to end the conflict, people would have to shake hands with their enemies, or those they believed to be their enemies.

INSAAN

You can only reconcile with the Taliban if you see the Taliban as fellow human beings who have had legitimate grievances, who have basic human needs which need to be met, who need to be loved and perhaps then they will not want to fight with you.

HOST

They decided to make leather cell phone pouches for young people in Kandahar.

HORSE

With a pen we wrote on one face of the leather the word Sol which means peace in Dari.

HOST

When the youth in Kandahar received their cell phone pouches, they called Insaan.

MUSLIMYOR

They said, “We couldn’t believe it. This is impossible. You have done an impossible thing. You are Hazaras. It blew our mind that you, not even knowing us, would demonstrate such love for us.”

HOST

Such a simple gesture had a huge impact. Little by little the volunteers were growing in confidence that they could bring Afghans together in the name of peace.

CHALLENGES AND LESSONS

HOST

These achievements didn’t stop skepticism from some quarters.

MUSLIMYOR

They insulted me. They accused me of telling lies. You can’t be volunteering. Tell us how many dollars you are getting from this.

HOST

Horse was ridiculed by his relatives.

HORSE

They would say, “You’re too young, you’re too small. These kinds of activities are mad.”

“You’re so small, whereas the politicians they are so big and powerful. If they can’t bring peace, what are you doing?”

HOST

They drew upon historic social change leaders for inspiration.

INSAAN

Ghandi has a quote: first they ignore you, then they ridicule you, then they oppose you, then you win.

HOST

They also drew lessons from their work.

MUSLIMYOR

When I joined the group, I realised that the youth who were there were working with good positive energy.

Then I realised that these presumptions and things that people were saying about the other ethnic groups was not true.

When we worked together, I saw that all of us were one, we are actually quite the same.

I learned from the group that it’s not important which ethnic group you come from, or which religious sect you come from, or maybe it’s not even important which religion you come from, humanity is what is important, truth is important. It’s important to be able to work together; it’s important to be able to help those who are poor and vulnerable. Gradually I made a decision that I ought to be working with such a group of young people.

HOST

Insaan and the young men remained committed to their philosophies despite the public criticism.

INSAAN

I was aware of the fact that the people who issued the threats were probably still angry, that they weren’t willing to meet me. I was wary and I was still being protected. I knew the threats could resurface at any time.

HOST

However, the local fears and suspicions associated with their work eventually caught up with them.

INSAAN

The person … broke into my room, dragged a gas cylinder into my room, and released the gas … then, with the gas filling the whole room, the person lit matches …

HOST

People from the village saw the house on fire and raised the alarm.

INSAAN

They had been in the fields and they rushed into my room. They were very frightened but they threw soil and water on the flames … I was on my way home at the time … I arrived at the house and my items that had been burned were … laid out on the ground, and the villagers were standing around looking at the whole scene … In my heart I thought “oh”.

HOST

In the days after the fire, strange accusations began to surface in the village that Insaan had set his own room on fire. Insaan sought advice from his colleague.

INSAAN

“Leave tomorrow. They are going to get you.”

“But I am innocent,” I said.

“That doesn’t matter. This is Afghanistan,” he said.

There are individuals and groups who are accustomed to the use of force and they won’t stop. They know what it takes to keep power.

HOST

Insaan realised he would have to leave the village and his friends, and he grieved this loss.

Although he decided to flee the mountains, he wasn’t ready to give up the struggle for peace.

HOST

After spending more than six years in the mountains, he decided he would relocate to Kabul where he could spread the influence and reach of the work.

MOVING TO KABUL

HOST

When Insaan left for Kabul he did not ask and he did not expect anyone to join him. However, three of the young men decided they would come with him.

HOST

The four of them agreed to live together in an apartment. The city had changed a lot since the last time Insaan had been there in 2004. Back then Kabul was a city flattened by war but at least there was hope the US would build a better future.

INSAAN

In 2003, the US turned their attention to Iraq and Saddam Hussein. They failed to stop a Taliban resurgence and to consolidate peace in Afghanistan. Reconstruction of the country was not a priority, and the Afghan people lost faith in the international forces and their promises of peace and democracy.

HOST

By 2011, the Taliban had regrouped and resumed hostilities. Stories of attacks, kidnappings and killings in Kabul were on the rise. The city had become overcrowded as refugees returned to Afghanistan and rural communities fled the fighting.

RESTARTING THE LIVE-IN COMMUNITY

HOST

During their first winter in Kabul, Insaan raised the possibility of inviting a Pashtun student to join their house of Hazaras and Tajiks. This was the first step to resuming the multi-ethnic community first started in the mountains. Paiman was the first Pashtun person to join Insaan’s experiment in Kabul.

PAIMAN

I noticed that the youth there spoke slightly different languages. Their accents were all different but there was friendship. I understood from then that friendship enables us to see everyone as human beings. Based on that I could see that we could sit down with one another, learn from one another, even live together. So I began to stay with the group.

HOST

Paiman was particularly critical how many drones had civilians in his own home province.

PAIMAN

The people began to see these computer-controlled planes would come every evening, close to evening, and they would hover in the sky around the area until the next morning.

My brother-in-law and his four friends had gone one evening to water their fields.

Close to midnight, the people in the village heard the sounds of bomb blasts. The next day they found the bodies of these 5 persons and the bodies were all burned and charred.

HOST

Paiman led the community in what became an annual kite-flying demonstration called “Fly Kites Not Drones”.

PAIMAN

Drones have a psychological effect on everyone in the area, in the village. Especially young people and children.

When my brother-in-law was killed, he was survived by his wife and children,

HOST

If anyone needs a reminder, these drone strikes were authorised by President Obama and conducted by military personnel sitting at computers thousands of kilometers away safely inside the United States.

PAIMAN

… my nephew says his father was killed by a computer.

HOST

As the Kabul Peace House grew – it grew in diversity. Many different ethnic groups started living together.

But peace isn’t some magic moment. It is a process – it is generated with empathy and openness over time. People had to work hard for peace, as did the house.

HAFIZULLAH

The first Pashtun I met was Paiman. Before that, my mental picture was Pashtuns are wild. They are killers. When I saw Paiman I thought he looked a little like us. But I wasn’t comfortable in the room with Paiman.

Paiman didn’t speak good Dari. He spoke Pashtu. I couldn’t understand Paiman’s Dari, so I gave up trying to speak to him.

It took about 3 months before I felt comfortable communicating with the Pashtuns.

HOST

The house was not an island. It was shaped by prejudice that lay outside the house.

MUSLIMYOR

I was fearful that the other ethnic groups in the community could be informers or spies.

That feeling lasted for about a year.

The Pashtun members would talk about how their people were suffering at the hands of the Taliban and that helped me to see that they are also not supportive of extremist views and practises.

Now, we are like brothers.

HOST

Personal connection overcame war-time rivalries. People decided to work together on community-building projects that would address inequality and injustice.

INSAAN

Gandhi himself said that his movement and advocacy work was only approximately 10% of his entire work for non-violence and essentially the majority of his work was what he termed constructive work. So non-violence is predominantly constructive.

CONSTRUCTIVE WORK

THE SCHOOL FOR STREET KIDS

HOST

Ever since Quetta, Insaan held a place in his heart for street kids. He felt that he needed to do something for what he didn’t do for Amaan and all the children on the border of Pakistan and Afghanistan.

INSAAN

One of the measures of society or of the human race is how we treat our children. Not just our own children, but all children. Surely we can understand that, right? They deserve more than what they are getting from humanity… We don’t have to spend money dropping bombs.

HOST

The community started a school for street kids. They initially enrolled five Hazara and Pashtun children from a displaced people’s camp as part of a three-month pilot program teaching literacy. Years later, in present day Kabul, the school had enrolled more than 100 boys and girls in classes of Dari, English, mathematics, nonviolence and tailoring.

INSAAN

These young children were all street workers before they joined the community’s school. To encourage families to enrol their children in government schools, we supplement the lost income of the studying child by providing monthly food gifts of rice and oil.

HOST

Arash is one of the street kids who joined the school.

ARASH

I have lived a life of poverty.

It was the tenth day of the religious festival called Moharram, and my father was working as a wooden cart street vendor.

He was pushing his cart near a mosque and the attack happened. My family tried to call my father but he never picked up his phone.

When I lost my father, I knew that I had to work every day in the streets.

I was 9 years old at the time.

HOST

While Arash was working on the street he was approached by Muslimyor and invited to attend the school.

ARASH

From the time I started lessons, I wasn’t very good in my writing or reading. Since then, with every year I have been improving.

From the second year I became familiar with the concept of nonviolence.

Non-violence is about not hurting other people, about preventing fights, about eliminating ethnic discrimination, and also taking care of the environment.

HOST

These classes were not just teaching students basic literacy, they were also providing lessons in how to be good people.

ARASH

One big thing that I have been able to learn and apply is that change starts with ourselves, within us.

I began to try in my own life not to discriminate against other people and to control myself when I get angry.

HOST

Before Hafizullah joined the community in Kabul, he had been an illiterate young child working on the street. His transformation in the community saw him become one of Arash’s teachers at the school.

HAFIZULLAH

There were 45 people in my class and even though I couldn’t read or write and couldn’t answer any of the questions, I would always be ranked 32nd.

The teachers who couldn’t accept my illiteracy would use punishment, like using a wooden stick to hit me on my hand, twisting my ears, hitting my head. There were various forms of punishment.

HOST

Hafizullah only began to learn to read and write in the classes organised by the community in Kabul. He now reads books about Gandhi and uses his own negative experiences of school to better teach the street kids.

HAFIZULLAH

When the street kids become naughty or make noise, I know that using punishment is not going to work. So I try different methods. I will shift them around the class rather than scold them or punish them.

When I see how we are helping the students to learn to read I get very happy.

HOST

This “constructive work” seeks to change how people live in society while building new relationships. They started with the school, but it went broader. They began a food cooperative, a peace park in Kabul, and they hired seamstresses to sew duvets which would then be donated to war widows and the poor veterans.

Community-building projects such as these attracted other young people, but many weren’t able to live in the house. Such a living arrangement was unusual for conservative Afghan culture which expects people to live within family networks. This was especially true for women such as Hojar who had begun to join the community’s activities.

WOMEN

HOJAR

At first I wouldn’t visit all that often. The house and the community were all male but there were female volunteers coming for some activities and causes.

The first time I visited the house I was with my mother.

I noticed how the space was not big and the rooms were not big and there were more people than what the space could accommodate.

HOST

Hojar had moved to Kabul to study at university. She was the first woman in her village to graduate, defying the expectation common in rural Afghanistan that she would become a wife and a mother in her teens.

HOJAR

I felt unhappy with the societal norm which believed that women are weak human beings, that they shouldn’t be involved in what men do or what people do in public places … and that our place was only to be in the home.

HOST

In the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, this is both a religious and a political issue.

INSAAN

In 2012, the religious council of Afghanistan announced that women are inferior to men… President Karzai’s office approved it.

HOJAR

Part of my persistence in going to school was really to defy society’s limitations.

HOST

Sadly, the university education she received didn’t meet her expectations. For Hojar, the community played the role in her life which she thought university would.

HOJAR

The community taught me to work with society and in groups, interacting with others.

HOST

We mentioned earlier that Hojar’s father had been murdered by the Taliban.

HOJAR

People, like myself, are seeking a way out of this fatigue, a way out of this endless fog of war.

Taking revenge will only lead to more grievances and more revenge and will ultimately end up hurting myself. With that understanding I can deal with those emotions.

Forgiveness is one way in which I and Afghans can find our way out of the endless war.

HOST

Hojar and two other women pioneered the first female-only, live-in community. They wanted to recruit more participants but it was difficult to find women who were allowed to live away from their family with strangers.

HOJAR

If we had been able to establish a female community which was similar to the male community there would have been, on a physical level, a clearer representation of our equality and our partnership to address ethnic divisions. We would have strengthened one another.

HOST

The female community stayed together for one and a half years. Their bravery paved the way for other women to join the group. Tara had heard about the group through a friend and became intrigued.

TARA

It was the first time I had gone out of the house without being accompanied by a member of my family or my parents other than going to school.

HOST

Traveling across town alone as a woman is not considered safe in Kabul. Tara’s father worked in the military and was particularly protective of her movements.

TARA

I catch a bus from my home to the centre. On the rare occasions when the bus is not full the journey is okay. But when the bus is full as it often is then it is very cramped.

Women frequently complain about the behaviour of men.

I always try to place myself in a safe position.

You have to be alert and smart to find those spaces.

HOST

Her initial visits to the community also challenged traditional Afghan cultural expectations of how men and women are supposed to interact.

TARA

There is this culture of muharram which is that the girl shouldn’t be speaking to a stranger if there is no family member around.

I felt shy looking at or wanting to speak to a stranger in the centre.

Even today, I am not completely comfortable with making eye contact.

HOST

So what encouraged her to keep returning to this community at great risk to herself?

TARA

It’s very difficult for a person to believe that this is the purpose of the group if a person hears it from afar. But when a person comes to the group and sees it for his or herself like I did then they would observe the volunteers working in different teams to build and create that world in a practical way.

HOST

It was the group’s implementation of nonviolent philosophies and practises that was most memorable to Tara.

TARA

Non-violence is not a small concept… it’s not going to be a quick process of believing it and practising it and making it popular in society. But I believe that every huge concept and practise starts small.

I am confident with time those small practises will become bigger and bigger until it will reach all of Afghanistan.

HOST

Nowadays, the community has an almost even number of male and female volunteers and they run a bicycle-riding school for women as well as other female-orientated activities. But the risks remain.

HOJAR

The fear of insecurity, of things just ending, is present for males and females … But the fear for girls, who are harassed or see violence, that fear is real and it is there.

CHALLENGES AND LESSONS

HOST

But remember we are in Afghanistan. Non-violence isn’t just a radical way of being but it directly confronts the war and violence that is all around.

INSAAN

We would wake up in the mornings and our alarm clocks were bomb blasts. Instinctively my eyes went to each corner of the room where the others were sleeping just to make sure that the youth were okay, that they were alive. And that’s a terrible way to start a day.

HOST

Insaan recalls one particular incident when he and Muslimyor were studying quietly in a room in the house.

INSAAN

The bomb blast was so loud that he literally flew across the room… The response from the Afghan government was the response the world has now to all forms of terrorist acts. We just kill. Kill, kill, just go and kill all of them… They came in their helicopters, they came in their planes. They were flying overhead. The windows were vibrating. The sounds were going boom, boom, boom and we couldn’t sleep.

HOST

What Insaan had discovered is that the difference between peace and violence isn’t just bombs. It’s in the actions of people every day.

INSAAN

This is how we as a world respond to fear. We fear the Taliban and all the terrorists. We ignore the terrorism which is inside us. And then we inflict more terror. We just make everybody afraid.

MENTAL HEALTH

HOST

These bombings, this chronic war, took its toll upon all Afghans.

INSAAN

Each and every person in community had their own way of manifesting their psychological challenges. Muslimyor would bang his head against the wall until he had to be restrained. Hafizullah… when he got angry on a few occasions… he would become so powerful in his rage that it would take two or three family members to hold him down… Asghar punched holes in the walls.

HOST

At times, little triggers sparked major conflicts in the house.

MUSLIMYOR

One evening, two young members of the community were arguing with one another and it escalated… in the end one of them picked up a knife and the other picked up the lid of a pressure cooker. We had to restrain them.

HOST

Insaan also felt the pressure of community life. He suffered bouts of uncontrollable rage which lasted for hours. He referred to this as his “Volcano”.

INSAAN

How ugly had I become? From all the accumulated stresses: from war… from bomb blasts, from attacks, from grieving. There were many things outside of myself that I couldn’t control…

HOST

The mental health issues in the house were substantial. A psychiatrist from the United States observed it first hand during a visit and said it was a 14 person psychiatric ward.

HOST

These psychological issues made community life unpredictable but they also invited the community to take on a much deeper solution. Even stronger relationships were needed. Insaan introduced peace circles as a way to foster understanding.

RELATIONAL LEARNING MODEL

MUSLIMYOR

Each member of the community would express their feelings about what was going on, about their concerns and their fears. It helped everyone see how we were all struggling, how we had shared worries and how everyone had feelings for one another. That really helped to strengthen our friendship.

INSAAN

Relationships can change everything. It’s the atomic power we haven’t tapped yet. Scientists discovered that when atoms fuse together, even though we can’t see this process, they release a power which is huge. The power of relationships can be atomic, even though we can’t necessarily see the effects of their fusion.

MUSLIMYOR

Over the years the members of the community have begun gradually to open our hearts, and … opening our lives to one another and allowing one another to learn how to consider one another as equal, that no-one is better than the other person.

INSAAN

Within three years I have started to see the community members learn to relate with each other that way. I have seen how these people’s narrow, conservative, rural, village, view of life changed into a world view… Within three years, the youth have learned the relational model. Now they can sit down with an international visitor or a person from another ethnic group or religious group and have a meal. It’s mind-blowing. If that could happen with everyone else in the world we would take concrete steps toward global peace.

HOST

These relationships were incredibly powerful. But even with strong relationships, tensions in the house were sometimes hard to manage.

MUSLIMYOR

Most of the challenges in the community were over cooking and cleaning.

HOST

Perhaps it wasn’t surprising that in an all-male house, in a country where women are expected to perform household chores, disputes occurred over household duties.

HAFIZULLAH

Up to that point in my life, I had never done any house work. So I thought, what? I have to do house work? I have to be on the cleaning roster?

INSAAN

Some of the community members resented having to do household chores. Some people didn’t cook on the day they were supposed to cook, or if they cooked, they didn’t clean up after they cooked. Some members refused to clean and others had to clean for them.

HOST

The rules of the community, which had been developed over many community meetings, stipulated how a member could join the Live-In Community.

Members were required to cook and clean, and a contract stated that under certain conditions the community could ask a member to leave. But like in all share-households, it was a lot more complicated than that. It was the small stuff that caused problems.

But instead of just passive aggressive post-it notes on the fridge, the conflict took on a broader meaning. Remember these were people who had been taught to hate each other. It led to accusations of discrimination and favouritism.

MUSLIMYOR

We don’t have the habit of talking about the problems.

We are fearful if we say it someone will get angry at us.

HOST

Rivalries between individuals, masked as ethnic or sectarian rivalries, threatened the harmony of the community.

INSAAN

Accusations were going to and fro across ethnic groups, accusations were thrown from perceptions of injustice within the community, unfair treatment… Even our regular program of trying to listen to one another more deeply was not enough… There was just too much pain.

HOST

Domestic arguments, traumas and the outside tensions raised by the existence of the peace house strained the internal relationships. Some members of the house stopped participating in community activities and household responsibilities. The live-in community reached breaking point. Dissenters who were no longer engaging with the group philosophies were asked to leave. In return, Insaan was threatened with retaliation.

MUSLIMYOR

I felt so discouraged by their various ways of treating us badly, like insulting us, spreading rumours about us, which were rumours that endangered our lives.

There were times when I didn’t think I could carry on with the activities… That was very disappointing, very difficult. The only thing we could do as a community … was to try to encourage one another.

HOST

There were calls from some of the group to retaliate the “Afghan way”, which meant using violence. The group feared their experiment was going to fail.

HORSE

Whatever they did, however they treated us, we tried our best to keep to our principles of not harming them, not responding violently.

INSAAN

There were threats and there are still consequences from that period of time which I continue to face…Did I want to give up? Yes. There were times when I thought, maybe it would be wise for me to leave.

HOST

Leaders like Muslimyor took guidance from the non-violence tradition.

MUSLIMYOR

Gandhi says a successful person falls but gets up again.

The successful person does not give up.

INSAAN

Historically the examples of slavery, of suffrage, of civil rights, all those things are bound to involve a struggle, problems, opposition.

INSAAN

Communities are like a wave. They never go away… The community evolves, the strength of the community stays, the effects including negative effects are part of the growth process, of pruning, of reforming, individually and as a group. Each and every attempt to understand this … is progress despite all our flaws, because we learn from our mistakes.

HOST

The community decided to transition away from the chaotic and self-destructive live-in community to a more structured and inclusive program based at a community centre.

INSAAN

The opening of the community centre was pivotal…

The centre enabled the community to refocus its activities in the centre rather than get embroiled in the community.

They don’t live together but there they have the space to work together, interact, become friends, practise, take action in teams.

People who weren’t living in community began to be involved in the activities every week.

They have become a family.

HOST

Insaan also believed it was a more replicable model for the rest of the country and an easier way for applying the principle of constructivism.

HOST

Nowadays, the community members work in teams which run different community-building projects. These teams operate under 3 core pillars.

INSAAN

1) Building green alternatives.

2) Building equal alternatives.

3) Building alternatives for non-violence and a world without war and weapons.

HOST

Teams are run by coordinators making decisions by consensus. There is no leader. The horizontal power structure is necessary to combat concerns of preferential treatment.

HOST

It has now been more than a decade since Insaan and the volunteers first started their experiments in peace and the country is as bad as ever: the Afghan government is in control of just over half of the nation, with a third of the country in conflict; a branch of the Islamic State has established itself in certain provinces; the international community has withdrawn significantly from the country and Afghanistan’s economy and political structure is fragile. The Afghan people have lost confidence in their government and are losing faith that peace and stability can be restored to their country.

So what hope is there for peace?

HOJAR

Peace will depend on whether the foreign powers that be will stop interfering, will stop selling weapons, using drones, planes to continue the war.

MUSLIMYOR

Peace is possible… But right now the people are not self-reliant. The people don’t have financial autonomy. So the powers then have a hook that they can use in providing financial aid and therefore fulfilling their own foreign agendas.

HOST

After decades of international and domestic diplomatic failure, Insaan and the group don’t trust the political negotiations between the US, the Taliban and other nations.

DONALD TRUMP

[38:45] We’ve been very effective in Afghanistan, and if we wanted to do a certain method of war we would win that very quickly, but many many – really, tens of millions of people would be killed. [39:58][13]

HOST

Regardless of any potential political agreements between international forces and the Taliban, peace will only endure if it lives in the community’s grassroots. It is only a bottom-up approach to peace-building that can overcome the deep-seated antagonisms between different ethnic groups.

MUSLIMYOR

It won’t come within our generation but we can work so there’s a possibility of peace coming in the next generation.

HOJAR

What we are doing now is laying foundations.

We can encourage each member to bring change within themselves, because personal change becomes a solid foundational change.

INSAAN

Afghans have great resilience and hope. Despite 40 years of war, they are still very resilient. They pass on hope to one another. They cling on to hope even when death is on their doorstep.

HOST

The future of Afghanistan looks precarious at best, but one thing is certain: if peace is going to occur in Afghanistan it must come from within, from the Afghan people.

INSAAN

I want to encourage anyone who would embark on such a process of relationships, raw naked human relationships, stick to it, don’t give up.

HOST

Changemakers is hosted by me, Amanda Tattersall. Remember to subscribe to this podcast to catch all our episodes. This is series 4 so there is plenty to be inspired by in our back catalogue.

If you want to learn more about the peace community, pick up a copy of Mark Isaacs’ book, The Kabul Peace House, available at all good bookstores and online at https://markjisaacs.com/

You can donate to the community by visiting: https://www.erc.org.au/afghan_project

You can also post letters to the community:

Letters For Peace, Edmund Rice Centre, 15 Henley Road, Homebush West, NSW, Australia 2140

This Series is written by Mark Isaacs, Kate Wild, Charles Firth, and Amanda Tattersall. Our audio producer is Jules W. Our sponsoring organisation is the Sydney Policy Lab at the University of Sydney. They break down barriers between researchers, policy makers and community campaigners so we can build change together. Check them out at https://www.sydney.edu.au/sydney-policy-lab/. We are also supported by the Organising Cities project funded by the Halloran Trust based at the University of Sydney. Like us on Facebook at changemakers podcast and check out changemakerspodcast.org for transcripts, our email list and updates on all our stories.

The ChangeMakers Organising School is a weekly training about social change designed for people who want to learn more, meet others and reflect on how we might change the world. It is free and runs every Thursday evening. Find out more by clicking on the training tab on the changemakerspodcast.org website.

Join our weekly email list to hear our latest musings, podcasts and training. Click on this button to subscribe: