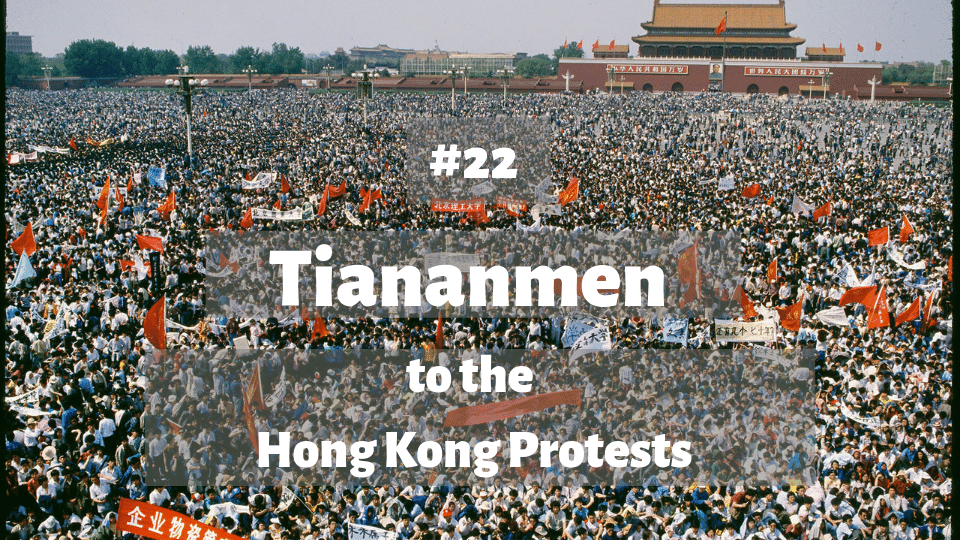

#22 – Tiananmen to the Hong Kong protests

From Tiananmen Square onwards, Hong Kong protesters have developed sophisticated protest strategies. We explore the long story behind Hong Kong’s protest life that has produced the 2019 movement.

Listen by clicking play above, or listen via an app on Apple, PodcastOne or Stitcher – or on most other podcast apps by searching “ChangeMakers.” Or use our RSS feed.

FULL TRANSCRIPT OF EPISODE #22 – FROM TIANANMEN TO THE HONG KONG PROTESTS

HOST: Today’s episode was recorded on the 4th September 2019, when events in Hong Kong were changing day by day.

On the 16 June 2019, two million people took part in a protest in Hong Kong.

BONNIE LEUNG: Well I have joined these kind of march for more than a decade.

Always we have a front banner at the front… When we leave the start point already there were a lot of people there, we could not move.

HOST: Bonnie Leung, is the vice-convener of the Civil Human Rights Front which helped organise the rally. Almost one in three people in the entire city were out in the streets that day.

BONNIE LEUNG: We could not move. The front banner could not move. So I just sent a message to my team-mates that the front banner is not at the front, we are simply a banner. I had never experienced anything like that and I was immensely immensely proud.

HOST: People feared an “Extradition Bill” – which could allow Hong Kongers to be taken to mainland China for trial. It meant Hong Kongers could no longer trust that they would be under the jurisdiction of Hong Kong’s distinct rule of law. Instead, the Communist Party of China could swoop in at any moment, and extradite a person to the mainland for their case to be held there, and their punishment to be determined by Beijing.

A protest movement first emerged in March 2019. But the June rallies were of a magnitude that shocked everyone. Two rallies each with over a million people.

BONNIE LEUNG: I believe the whole Hong Kong Island were full of people who just want to protest not to do anything else but just to protest… We could sacrifice our life for this. So who knows what would happen.

HOST: For those in the West, these enormous protests looked one-off. But Hong Kong – like many Asian cities – has a culture of mass protest and civil disobedience. Today we are in Hong Kong. The anti-Extradition movement may look like it came out of nowhere, but it was built over decades. We came here in July and have kept in touch with local leaders ever since. The result is this, a special series on Hong Kong. And, for those interested in Hong Kong, you should also check out episode 12 of ChangeMakers which covers the 2014 Umbrella Movement. But to understand Hong Kong you need to go back to Tiananmen Square. Let’s go.

I’m Amanda Tattersall, welcome to Changemakers, the podcast telling stories about people changing the world. Our episodes about Hong Kong were produced by Samuel Chu, and this episode was written by Mark Isaacs.

We are supported by the Sydney Policy Lab at the University of Sydney. They break down barriers between researchers, policy makers and community campaigners so we can build change together. Check them out at sydney.edu.au/policy-lab.

And you can sign up to our email list at changemakerspodcast.org, follow us on twitter @changemakers99 or on Facebook at Changemakers podcast.

HOST: Hong Kong is and isn’t part of the People’s Republic of China, and it is and it isn’t part of western democratic capitalism.

Hong Kong became a colony of the British Empire at the end of the First Opium War in 1842 and the United Kingdom didn’t transfer sovereignty of Hong Kong to China until 1997. This complicated history keeps Hong Kong in a strange grey area between the two political systems.

LEE CHUCK YUEN: People in colonial time, we will not say that we want the British to remain though definitely we are, at that time, very fearful of the Communist China authoritarian rule. And many people escape to Hong Kong and all the generation, my father generation, all escape from China to Hong Kong and in the 70s there’s still a lot of people escaping poverty from China and Hong Kong.

HOST: Chairman Mao Zedong’s attempted to transform China from an agrarian economy into a socialist society in the late 1950s, called the “Great Leap Forward.” It damaged China’s economy and caused widespread famine and millions of deaths. Mao’s subsequent Cultural Revolution purged capitalist and traditional elements from Chinese society in order to preserve Chinese Communism. This led to widespread persecution and displacement and saw many people flee to Hong Kong, which was still under British rule.

Lee Chuck Yuen is the head of the Confederation of all the independent unions in Hong Kong and has been a democracy activist for more than four decades.

LEE CHUCK YUEN: My father generation tend to say don’t know nothing to do with politics. They are afraid of politics and therefore they just want to stay on without any worry that you know raise their children. They have not thought of anything about democracy. That was the British era, you know colonial time, there are no political representation for anyone in Hong Kong… But then in the eighties is our era, you know in a way when we were young.

HOST: Although the eighties was “their” era, Lee Chuck YUEN’s personal story of activism began a few years before then.

LEE CHUCK YUEN: You know I think back in the late 70s, I was in the student movement and then studying civil engineering at that time, like any university student you begin to think ‘what are you going to do with your life?’ And I decided I should do something for the social justice and the poor in Hong Kong. That time is the time when I start to really do labour organizing.

HOST: For Lee Chuck Yuen it was in fighting for people’s rights at work that he realised the importance of democracy.

LEE CHUCK YUEN: Workers, of course, need representation and need to have democratic right to change and improve our conditions and to fight for social justice. How can there be social justice without democracy? So very naturally we are also part of the democracy movement in Hong Kong.

HOST: The desire to express political democracy and self-determination in Hong Kong became pronounced in the 1980s when discussions about the handover process from Britain to China first began.

LEE CHUCK YUEN: So in the early 80s there’s a discussion about the future of Hong Kong – you know what sort of future we want. So the natural decision for our generation of activists is that we want to fight for democracy in Hong Kong. We want to get rid of British rule but we don’t want to live under China and we want to have a democratic Hong Kong, so that we can resist communist China.

HOST: During British colonial rule, the Hong Kong people never had universal suffrage. The Governor was appointed by the British crown as their representative in Hong Kong and they ran the Government’s Cabinet. Democratic reform did come thanks to democracy activists like Lee Chuck Yeun, but the avenues were limited.

LEE CHUCK YUEN: When I graduated no no election at all. But then during early 80s the colonial governments start to say oh maybe we’ll give you some sort of election in the district level without power.

HOST: Reverend Chu was also a big player in the democracy movement. For him democracy was the means by which people could improve issues in their daily lives, especially in the poor communities that he worked with in Chai Wan on Hong Kong Island.

REVEREND CHU: In the early days, in 1974 when I came to Chai Wan – the main focus of my work was to tend to the daily life issues for those in the lowest class of society – how we can improve their quality of life and how we can improve the larger community. So I came here to serve the poor and the impoverished.

HOST: Reverend Chu is being modest here. He was orphan who had been homeless. He didn’t just serve the poor, he was one of them.

REVEREND CHU: I fought for access to healthcare, to housing and to transportation. That’s where I started – if my church is in Chai Wan, what impact does the church have in the community? … I started to address the issues not only inside the church but also outside, working alongside the residents and neighbour to solve these problems.

HOST: So whether you are organising poor workers for better conditions or poor people for better communities, you can’t do any of that without democratic rights. Reverend Chu believes that the 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration, brought Hong Kong democratic politics to life. As part of that agreement, China guaranteed Hong Kong’s distinctive economic and political system for 50 years after the Handover. It became known as “one country, two systems”.

REVEREND CHU: 1984, the “handover” became the primary issue in Hong Kong. Many Hong Kongers emigrated; many of them were scared. My work expanded from my own small local community to the broader Hong Kong community. The issue impacted not only the residents in Chai Wan; the issue affected everyone in Hong Kong. If we can advocate successfully for a democratic political system, under which everyone can live prosperously and peacefully, I felt like that was also my responsibility.

HOST: In July 1984, the colonial government proposed the first large-scale constitutional reform in its history. Democracy activist, Miranda Yip, explains.

MIRANDA YIP: Just starting from I think, 1980s, we started to have some people being could be elected into the Legislative Council …

HOST: But the way they were elected was through functional constituencies. These allowed members of a professional or special interest group to elect their own members of the Legislative Council.

But it wasn’t direct election. The professional groups that were allowed were from the banking sector, medical sector, engineering and they excluded the working class.

BONNIE LEUNG: In short it is only the most powerful people in Hong Kong could vote. It is a very (…um) complicated and weird system. Why it exists was because first of all the British government … didn’t want to give us a democracy. And secondly the … Chinese government also doesn’t don’t want us to have democracy. So this weird and totally undemocratic functional constituencies existed and sustained until now.

HOST: Lee Chuck Yuen spent the 1980s campaigning for universal suffrage.

LEE CHUCK YUEN: Very naturally the first fight we have is for … democratisation of the Legislative Council. The 88 democracy direct election movement.

HOST: The idea of “direct election” contrasted to “indirect election” used by the functional constituencies.

LEE CHUCK YUEN: We have a coalition of NGO civil society and also district council election and they are starting to political party formation also at that time. So all these political parties civil society will join together to fight for direct election 88

HOST: The Handover created a political opportunity – and the democrats seized upon it.

LEE CHUCK YUEN: On the one hand we fight from the British the direct election and … on the other hand we are fighting against the Chinese Communist Party basic law and to have a mini constitution that guarantees our right.

HOST: Lee Chuck Yuen and the democracy movement didn’t achieve their goal of direct election in 1988. But they did create a political base for democratic campaigning. And that movement soon became captivated by the rise of idealistic students fighting for democracy on the mainland. The students gathered in a place called Tiananmen Square.

LEE CHUCK YUEN: … we also found that you know we as Chinese in Hong Kong, we should fight for democracy in Hong Kong so that it can be a window for China. We want to change China also.

HOST: 1989 was a big year. Global forces were shifting. There was the fall of the Berlin Wall and the Soviet Union’s Iron Curtain. But before all that – there was change in China.

LEE CHUCK YUEN: We feel that at that time the mood … in 88 is quite a good time in China. I mean good time in the sense that seems things to be seems to be losing out up and you know there are more political discussion about the future of China.

HOST: So what was happening in China in 1989?After the death of Mao Zedong and the end of the Cultural Revolution in 1976, the country was mired in poverty. Economic production had slumped. But the foll owing decade, major political, economic and social reforms returned China to prosperity. By the end of the decade, a democratic movement among university-educated Chinese flourished.

LEE CHUCK YUEN: We in Hong Kong naturally are very much into the human rights situation … there is a sort of a general mood that you know China is losing now. We have to support human rights in China And then 89 broke suddenly broke out the death of Hu Yaobang and and everyone was suddenly woke up in Hong Kong and say oh wow this is the biggest demonstration that China ever had. Of course China had very big demonstration top down. You know like Mao Zedong stage the Cultural Revolution and all of this are very much a top down type of movement. But this time is nothing top down is really bottoms up coming from a student and coming from the years of you know democratic discussion among the student in Beijing about the future of China and they come out and say that they they commemorate the death of Hu Yaobang and they will ask for freedom and democracy.

HOST: Hu Yaobang was a high-ranking leader of the Chinese Communist Party who pursued economic and political reforms in the post-Mao era. He became the enemy of several Party members who opposed greater transparency and free market reforms. When he died due to a heart attack, his enemies tried to tarnish his memory and reputation.

Reverend Chu remembers the response.

REVEREND CHU – As the students were memorializing Hu Yaobang into the month of April, many of the student protesters were returning to or have already returned to schools for classes. But then, what we now called the “426” editorial appeared on the frontpage of the party’s official newspapers – “The People’s Daily” on April 26, labeling the students at Tiananmen square and what they are doing as “anti-government” rioting. The students immediately felt – in what ways are what we doing “anti-government” or a riot? We are memorializing Hu Yaobang and we are against public corruption and cronyism and demanding democracy. So, after April 26, all the students came out again, including people from all sectors and parts of the city. And over 1 million came out to Tiananmen Square, suddenly Hong Kongers were alerted and alarmed that this movement was not as simple as it appeared.

HOST: It’s important to understand what had just happened. There was a protest, Beijing officials condemned it, trying to repress it. What happened next? The opposite to what the Government had hoped. More students came out in response. The curfew, in effect, turned a medium sized movement into a monumental one.

This might have been the first time that this dynamic played out in China, but it would not be the last.

The response to Hu Yaobang’s death spread to Hong Kong.

LEE CHUCK YUEN: The first sort of groups in Hong Kong that responded to the student movement in China was the Hong Kong Federation of students. So that generation of student activists begin to go to China to support the students. We have already a coalition to fight for the eighty eight democracy direct election. the Labour trade unions the party the political party the church religious group social social organization housing and the rest of that organization. So in that background … everyone come together and begin the demonstration.

HOST: Democracy fighters in Hong Kong stood in solidarity with Chinese demonstrators.

LEE CHUCK YUEN: So when the students go on hunger strike … we have a march in Hong Kong of 1 million. May 21st was the biggest one or the biggest one in in Hong Kong. Then May 28 there will be a worldwide march for democracy.

HOST: And it wasn’t just protests being organised.

LEE CHUCK YUEN: … we have raised on one democracy concert with all the artists in town. We raised twelve million Hong Kong dollar in one night. And together with the money coming in we have already come up with 22 million. … So then there is a problem you know. Someone had to go to China to visit the group. So I was the one that was chosen to go there.

HOST: Lee Chuck Yuen got on a plane and arrived in Tiananmen Square on 30th May with one million Hong Kong dollars.

LEE CHUCK YUEN: We visited Tiananmen Square. Told them that we Hong Kong people are really very supportive of movement and we hope that you know they we can together can support the democracy movement in China.

HOST: Hong Kong became like the Alibaba for the students in Tiananmen.

REVEREND CHU: Whatever the needs were, many tents and supplies were donated and then shipped from Hong Kong. And as it continues, everything was still peaceful, they were still just making the same reform demands.

HOST: But things were getting dangerous, a new dynamic had developed 10 days earlier.

REVEREND CHU But then came May 19, which was a pivotal turning point – when in the early hours, the Chinese Premier, Li Peng, declared martial law. Once martial law was declared, Hong Kongers became very anxious – because once martial law was declared, the movement now faced a very critical and dangerous situation.

HOST: Hearing this, it’s hard not to see the eerie similarities with Hong Kong in 2019 and the talk of ‘state of emergencies’ and displays of military strength on the border and in Hong Kong.

REVEREND CHU: When we witnessed the vehement way that Li Peng had announced and imposed the martial law, we immediately started to organize. That same day we formed the group “Hong Kong Christians In Support of Patriotic Democratic Movement in China”; another larger organization was also formed – the “Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China”.

We marched, we protested, we had prayer meetings all over Hong Kong – all in support of a peaceful resolution and to avoid a violent crackdown of the students by the Chinese government. There were 24-hour prayer vigils all over Hong Kong.

After the groups’ formation, sometime in May, we felt that it would be important to send someone to see what was actually happening on the ground and I was sent to Tiananmen Square from Hong Kong to gather first-hand intel.

HOST: On 28 May, Rev Chu travelled to Beijing. He met with student leaders and got to discuss with them the next steps.

REVEREND CHU: I met with Wang Youcai, and spoke with him at length. Wang was one of the hunger strikers and, he was on the 21 most wanted by the government list after the June 4 crackdown. We talked about the movement and he explained that the movement has now gone on for a lengthy period and he felt like it must shift toward base-building education – it was time to spread out and conduct democratic and civic education in the rural villages.

HOST: To any keen listener, Yang Youcai’s idea has remarkable resonance. It sounds almost identical to the 2019 strategy. Today protesters have said they need to be like water, that they need to be fluid, moving from place to place, based on what is required and not stuck in a square. It’s almost like that today, the ideas of Tiananmen have come full circle.

REVEREND CHU: So we decided to give them the funds we had raised in support of that work, hoping that they would truly start in the villages and start the democratic education at the base.

HOST: Before Rev Chu returned to Hong Kong on 3rd June he gave the student leaders a message.

REVEREND CHU: I met with Wu’erkaixi ئۆركەش دۆلەت 吾爾開希 right there along the streets. I shared with him that firstly, the student movement has already succeeded. Where it has succeeded is that it captured the hearts of all the overseas Chinese – their patriotism, their hope for a democratic China and for an end to public corruption – the movement ignited all of their passions. That’s a success – Chinese people all around the globe had gotten involved because of the movement.

Secondly, they are about to face a very difficult, sobering and dangerous situation ahead – the situation they find themselves in is that Tiananmen Square was already surrounded by the military and that a crackdown and clearing of the square was a matter of when not if. I told him that you have to prepare for the crackdown coming.

But none of us – not even the students in the square – ever thought that the crackdown would be with tanks, with real guns, shooting and killing its own people.

HOST: Rev Chu had to quickly return to Hong Kong because he had to minister a wedding. But during the reception no one could concentrate – the first news came from Beijing.

Guests were crouched over a crackling radio on one of the dinner tables.

REVEREND CHU: News broke that shots have been fired. We knew that the situation would start to spiral – because once you fire once, it made clear that the government will use violence and force to clear the square no matter the cost.

We were all deeply saddened and heart-broken.

HOST: It was even worse when they turned on the television.

REVEREND CHU: We were beginning to see images on televisions – images of the military advancing and students retreating. When we got back home later in the evening, we watched the numerous students who were injured, some of the injured were being transported and pushed along in wooden carts, all of them dripping with blood. Ambulances racing to-and-fro between the square and hospitals, scenes of the injured and the dead at the hospitals – we were all shocked and sad. We didn’t really know what we can do.

HOST: Lee Chuck Yuen was there.

LEE CHUCK YUEN: Come June 4th I was in the Tiananmen square and … I was in the camp of the Workers Federation at that time and people tell me that I must go back to the hotel because the army are coming in and they are going out to see what is happening and want to stop the army from coming in. Of course, they cannot stop the army from coming in. They had already started to shoot quite some distance away from Tiananmen Square. People are running because the army starts to shoot on from both sides the east and the West and squeezed to the middle. there’s no announcement there’s no no communication…But then people know and then they come back to the square and tell people that the army is coming in and starting to shoot. And it was a shock. So it’s quite like what happening now. You know when the student young guys are there, you know the workers and all the people outside want to protect the students so they go out and to say that they have to block the army and the tragedy actually happened on the street not inside a square.

HOST: Lee Chuck Yuen stayed at his hotel that night, not wanting to be killed by an all powerful army. The BBC’s Kate Adie reported this from the scene.

CLIP https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kMKvxJ-Js3A

KATE ADIE: The noise of gunfire rose from all over the centre of Peking. It was unremitting. On the streets leading down the main road to Tiananmen Square furious people stare in disbelief at the glow in the sky listening to the sounds of shots. And then as troop lorries were seen moving down the road there was gunfire from those lorries. The troops have been firing indiscriminately but still there are thousands of people who will not move back.

A huge volley of shots just as I left the front line caused panic. The young man in front of me fell dead. I fell over him. Two others were killed yards away.

There was confusion and despair among those who could hardly credit that their own army was firing wildly at them….

The air was filled with the shouts of “fascists, stop killing”.

LEE CHUCK YUEN: In the morning … you can see the people you know with the tricycle coming with bodies and injured people. My next problem is where was all the student Hong Kong. They have not come back. So we don’t know where they are. And I think they are in the Tiananmen square. And what happened in the Tiananmen square? No one knows because the light went off. And of course later we know that there’s some negotiation of (name unknown) and the army and then most of them are allowed to go out of the square and and leave the square. And then I find out the students was in the hospital the Hong Kong student. Then in the hospital … the horrible thing you see you know the injured people there… There are bodies inside and you know stacked on there. So it’s quite a horrid horrible sight. And then I get a student back to the hotel and then we have this thing of how to leave China.

HOST: Martin Lee, a Hong Kong politician and barrister, chartered a flight to Hong Kong for Lee Chuck Yuen, the students, activists and the Hong Kong press. Lee Chuck Yuen and his group had the chance to get out.

LEE CHUCK YUEN: When I was in the airport and we go through the custom and then we go on the plane. And then I was arrested from the plane… They told me that if I don’t leave the plane the whole plane cannot leave. So they make the hundreds people in on the plane the hostages. So I have to leave the plane… And I was in the hand of Communist Party and of course … I don’t know what would happen… They put me back in a hotel and the next day they bring me to a sort of a school sort of a college. And then in the basement they start to you know interrogation and talk with me and you know blah blah blah and then we talked for the whole day and asking me what I’m coming to do. And I said that you know of course I support the student movement.

AMANDA: What did you think could happen? What was going through your head?

LEE CHUCK YUEN: I can do nothing. I can only pray. I think they have not yet decide how to deal with me. So in a way that’s good in the sense that I’m not lock up in the cell or torture. In that sense. So but psychologically I was very insecure of course fearful cause this is a regime that just massacred the people. And killed thousand of them… but then after three days I think they let me go by asking me for a confession. So a confession in the sense of saying that I’m wrong. So I have signed a confession that I was wrong. And then I was able to come back.

HOST: Historian of China, Hans van de Ven, summarises the Party’s motivation behind the massacre.

HANS VAN DE VEN: https://player.fm/series/talking-politics-1423621/talking-politics-guide-to-the-chinese-communist-party

[15:29] The thing about Tiananmen that we don’t have a grasp on is how widespread it really was. [15:35] [6]

[15:42] It was all across the country and there was paralysis within the Party which is why it did not act earlier. Deng Xuo Ping who decided we have to act and if we are going to act we have to do it seriously. Blood needs to be spilled and that will buy us a couple of decades of internal quiet… [16:14] [32]`

HOST: A couple of decades …

HOST: Tiananmen became a dramatic moment for thinking about how to contest authoritarianism. Lessons emerged that often got reproduced. Not necessarily intentional, or planned, but Tiananmen defined most of the movements that followed.

The first lesson was recognising the power of localised organising.

REVEREND CHU: At that time, some of the students from the universities didn’t want to just stay at the square – they wanted to go out and teach about democracy, human rights to the masses. And I supported that idea – I agreed with their strategy. We needed to start in the base – at the base level of society with democratic education. So they already had this notion during the movement, but it was too late by that time. Regretfully they didn’t have time – they didn’t have the opportunity to implement the strategy to spread out. The massacre on June 4 ended that. Also because in the aftermath, the continued crackdown and state-monitoring and repression was extremely tight. Even now, the work cannot be done.

In fact, back in 2014, we had raised this idea and strategy of “be like water”. From what we have learned watching different movements around the globe, we felt like this was necessary. If you all stay in one place, or have one singular leader, it was very easy for them to arrest you. Or you would have what happened in 2014, where the government let you occupy the street for 79 days – letting the occupation lose purpose and meaning. So we did propose that we should be like water and flow down and into different streams into different communities, to work slowly and methodically in local neighborhoods. But the strategy could not have succeeded – the idea was still very new and very fresh, so we couldn’t pull it off.

HOST: Be water. It didn’t land until after the 2014 Umbrella Movement, but now it defines the method of the 2019 uprising. A second lesson from Tiananmen was the role of large, peaceful demonstrations.

REVEREND CHU: On June 4, we organized a large-scaled black march – a black-themed rally in honor of those killed and injured. The march and rally took place in Happy Valley with tens of thousands of Hong Kongers, to remember their fallen comrades.

HOST: In Hong Kong, there was a million person march in the lead up to Tiananmen massacre. Unlike the fixed occupation of Tiananmen Square, big protests in a single day were seen as safer as they were less confrontational. Hong Kong Protesters also recognised that they had an advantage compared to their allies on the mainland because they had some democratic rights and the rule of law.

REVEREND CHU: That’s what we fought for because we know deep down that if this is the kind of regime we will be facing, we must have a democratic system in place to safeguard and protect our human rights, democracy and freedom. So that’s the movement that we started – and in 1991, there were a selective number of legislative seats that were directly elected.

HOST: But the story Tiananmen did not end in Tiananmen Square.

Weeks after the massacre, Rev Chu got a phone call from a journalist who had taken his business card when he visited the Square. Students had been calling the journalist wanting help to get out of the country. The journalist phoned Rev Chu desperate for help.

Rev Chu pulled together a disparate network of democracy supporters to build an underground railroad called Operation Yellowbird. The plan was to use smuggling ships to get people out of China via Hong Kong and then fly them to 3rd party countries.

The name came from the Chinese expression “The mantis stalks the cicada, unaware of the yellow bird behind”.

REVEREND CHU: At that time, we used very simple methods. The reason is because we were just everyday common people, we were not spies, we didn’t have any training. So at night, how do we know if the boat has arrived? So in the darkness of the night if we were expecting an arrival, what can we use to be able to see? So that’s when we used infrared cameras. We also use devices to sweep for bugs. Whenever we are meeting, we would sweep the rooms, checking for any listening devices. We would also take our cell phones apart and stored them away during meetings. We also used coded communication – all of our communication were single channel and one-directional. Each specific code was only known to the one person on the other end of the communication, no one else knows. That allowed us to operate more easily.

HOST: Rev Chu says they were common people, but I don’t buy that. These guys might have been operating in a world of fax machines and pagers but they cleverly subverted every tool they could, for their democratic purpose. Indeed I don’t see much difference between their creative use of pagers and infrared goggles back then, and the way in which 2019 protesters use digital tools like Telegram messages, airdrop or how activists repurpose easy to find road work equipment like orange Road Cones to extinguish tear gas canisters. But it wasn’t just technology that was on their side, it was many of the Chinese police.

REVEREND CHU: We call it “one eye open, one eye closed”, the truth is that many of the Chinese police were sympathetic to the students; everyday people and the police were all sympathetic. So even they have spotted a student leader, they would let them pass. And in Hong Kong, we had already negotiated with the Hong Kong government, the different consulates already committed to receiving the students, so everything happening in Hong Kong was done in part with the Hong Kong government.

HOST: The PRC found it difficult to round up students in the aftermath of Tiananmen. This is because they had lost the support of many of their own police. Their brutal over-reach actually fractured their monopoly on violence, if only briefly. Even a totalitarian state has its limits. Yellowbird began in June 1989 and continued until 1997, successfully smuggling more than 400 dissidents through Hong Kong, and then onwards to Western countries. Every year since 4 June, memorials have been held in Hong Kong. The 30 year anniversary occurred 5 days before the first million person march in June 2019. For those who were old enough to remember it – Tiananmen is an inescapable reminder that you can’t under-estimate how violent the state can be.

Seilong, who is a part of a Hong Kong mothers protest group, could see the shadow of Tiananmen at the 2019 protests.

SEILONG: We don’t want to become Tiananmen Mothers. We do not want those tragedies to happen.

HOST: But the fear of Tiananmen is experienced differently depending on your age.

AMANDA: To what extent is that a fear that people in Hong Kong have about protest. Do people ever worry that that could happen here?

MIRANDA YIP: In 2014 when the Umbrella Movement came in Hong Kong. we were so worried that the government would do the same, sending you know it could be troops or or you know police.

There was this tension between the older generation of activists and the young generation where you know they might have not experienced themselves the Tiananmen.

HOST: The march for formal democracy in Hong Kong continued post Tiananmen.

AMANDA: How did 1989 change the fight for democracy in Hong Kong?

LEE CHUCK YUEN: After eighty-nine the people are really scared of the Communist Party. So it emerged into two different branch of movement or demand. One is to speed up the democratization of Hong Kong. And the other is to leave Hong Kong to find exit. So the elite in Hong Kong would want to have a British passport. But how about those who remain?

HOST: Lee Chuck Yuen argues that this created a class divide in Hong Kong. The elite fled while the working class had no choice but to fight for democracy. After Tiananmen, Hong Kong’s democracy movement split into two parts.

LEE CHUCK YUEN: We have decided to form another coalition called the Hong Kong Alliance and Support of Patriotic Democratic Movement in China. One will be on Hong Kong and the other will be on China. I’m at that time the member of the Hong Kong Alliance … And every year we have the candlelight vigil that commemorate June 4th. one of the role of the Hong Kong alliance … is to highlight all the struggle of the Chinese dissidents and also the human rights defenders in China.

HOST: In 1991 Hong Kong had its first direct election. The British colonial government had only allowed 18 members to be elected, which was less than a third of the chamber. The democracy movement had been fighting for half.

LEE CHUCK YUEN: So it become … a power game. In the past Union power, street power, we have been doing that for many years and now the people at that time start to say that apart from a street power we need to have political power.

HOST: So political parties formed. The pro-democracy camp won 16 of the 18 directly elected positions. It was a race against time. Handover was 6 years away and they knew it would be their best chance to win democratic concessions. They chipped away at the system. Functional constituencies were opened up – allowing more avenues for working class people to participate. The democrats goal was to have in place a separate system in Hong Kong – it might be part of China but it would embody many liberal rights around rule of law and have some direct elections. But the question was, what would PRC do once Hong Kong was handed over?

BONNIE LEUNG: The pan-democratic was at their most powerful period before the handover. But of course as Beijing was so pissed about that the whole reform and right after hand over the original Legislative Council was uh scraped.

HOST: That’s right. The entire Legislative Council was abolished overnight.

Lee Chuck Yuen was a Legislative Councilor at the time.

LEE CHUCK YUEN: What happened in 97 is that we all have to leave the electoral. And then we have to be re-elected one year afterwards. So the whole year was empty and so that year they can do whatever they want. The Beijing government.

HOST: Even when elections resumed there were challenges.

LEE CHUCK YUEN: After the handover you know then everything is stuck. In the sense that. Stuck without any democratic reform.

HOST: But soon, a new piece of legislation would energise people’s participation in the democratic process.

LEE CHUCK YUEN: In 03 the government decided that they have to make a law on national security. The infamous the article 23 of the basic law and the Basic Law Article 23 say something like you know Hong Kong need to have a national security law against treason against sedition against subversion and things like that.

HOST: Like the Extradition Bill of 2019, Article 23 of the Basic Law tried to create powers that allowed for the punishment of people who acted against the authority of the People’s Republic of China.

Debate fired up around terrorism and sedition in 2002 and by February 2003, Chief Executive Tung Chee-hwa proposed a piece of legislation that sought to define seditious conduct very broadly. History doesn’t repeat but it sure does rhyme

The Bill was met with anger. People like Lee Chuck Yuen were very concerned as it outlawed the solidarity work he did supporting Chinese dissidents.

LEE CHUCK YUEN: So anyone practices freedom of speech in China will be a dissident and will be committed to become a subversive crime. So how can you in Hong Kong accept that this China law coming to Hong Kong? And then we will say that anyone in Hong Kong which we have so many protests against China, people like us who will be then a dissident and then we will be can be charged with subversion law.

HOST: Knowing that their Legislative Council was stacked against them, Hong Kong people knew that the only way to stop the Sedition amendments was on the streets. They built another coalition.

LEE CHUCK YUEN: The Civil Human Rights Front was formed with all the political party, the NGO, the civil society, church group and and all these groups come together … then we start to … organize demonstration and in a way we are good at that to organize a demonstration because the Hong Kong Alliance in 89 …had done a lot of demonstration and even after 89, every year we have some demonstration on either democracy or the candlelight vigil.

HOST: Like with Extradition, the marches started small – overtime building more support. They used lawyers to explain to the public why the law was harmful to Hong Kong.

LEE CHUCK YUEN: The lawyer is very important in this sort of fight. When the lawyers say something the people will believe them and they do not believe in the government.

HOST: Imagine a world where lawyers are considered trustworthy. The sedition protesters used “new” technology.

LEE CHUCK YUEN: At that time is no social media but there’s starting to have email and the email is at that time what we call snowballing of email. People begin to share email and then to to fight against this law.

HOST: The Chief Executive had a plan to take the sedition proposal to the Legislative Council on 9th July.

But that plan was changed by the people. On the 1st of July 2003, the anniversary of the handover, people took to the streets outside the Legislative Council.

LEE CHUCK YUEN: On July 1st we have the demonstration and that is a half a million people demonstration.

HOST: Miranda Yip was there.

MIRANDA YIP: It was like the first time that such a huge turnout protest in Hong Kong…the whole Hennessy Row and all along from Causeway Bay to Central were all packed with people.

HOST: It was exciting, but also tense. At the time, Bonnie Leung was a high school student.

BONNIE LEUNG: The last time …before 2003 when we have this kind of mass protest was because of the uh the Tiananmen Square massacre … And uh so that was the very first time Hong Kong people was so uh scared and cares so much about our city.

HOST: But the public pressure worked. The bill was withdrawn. The street-based strategy was successful.

BONNIE LEUNG: And also that was the first time ever Hong Kong government and Beijing governments saw Hong Kong people can be cared so much about our city. And would take to the streets. So I guess at that time it was a shock to both camps.

HOST: They won, even with only a minority in the Legislative Council, or LegCo for short.

LEE CHUCK YUEN: So it’s the same is quite similar to what happened now. We are always in the minority in LegCo so people know that no matter what happened inside L egCo we will always lose. So we have to go on the street to mobilize people power against this sort of a draconian measure.

BONNIE LEUNG: The government soon withdraw that bill at that time they used the word withdraw and then uh a few months later uh chief executive Tony Chu stepped down with an excuse about his health issues.

HOST: Hear that – withdrawal. Not describing the Bill as suspended, or dead. The Chief Executive used the technical, correct procedural term that kills the Bill. And then he stepped down.

It’s amazing how that decision in 2003 de-escalated the tension and returned calm to Hong Kong

The protesters had won. But they were also aware of the limits of what they had done. A pattern was starting to emerge.

LEE CHUCK YEUN: It is always a case at Hong Kong whereby we want democracy but denied it and was frustrated. But then when the Chinese Communist Party want to do something against the freedom they are met with a big fight from our side and they may not succeed. So to some extent we are able to defend our freedom but we are not able to get democracy and we are stuck in this very much of a system which is very unfair we are stuck with a nondemocratic system.

HOST: It might be one country two systems, but it is a pretty frustrating system to live with.

Without an alternative, mass protest continued to be an essential tactic of the democracy movement.

LEE CHUCK YUEN: So every big movement you have a one generation of activists and the one generation activist will have to choose what they would do after that big demonstration. So and night that in that generation as 2003 many people began to come off to become interested in politics and they began to run for district council election and legit council election.

HOST: So let’s recap where we are at. We’ve had two enormous moments of protest each producing a new generation of young democracy activists.

We had Tiananmen and the 89 activists who leveraged their protests to lock in the first pieces of Hong Kong’s system of partial direct democracy.

We then had the 2003 generation who organised mass demonstrations that successfully protected Hong Kong’s distinct ‘system.’

By 2011 a new generation was emerging. A group of high school students led by Joshua Wong began protesting against a proposal for “moral and national education” – meaning pro-Communist education – that was proposed by the Hong Kong government.

MIRANDA YIP: It was started with a curriculum, the curriculum itself … were just more emphasizing on how great and grand China is and how we should love our country. The details about you know June 4 and Tiananmen or even other more critical you know ways of seeing how China has become the big power was totally not there. They were told that they need to sing national anthem. And yeah and raise a flag. When we recall like how mainland China has been in the Cultural Revolution and you know what you kind of brainwash people to absolutely you only see the positive side of the country. That to us is just absolutely you know across our bottom line.

HOST: Joshua and his fellow students built a movement to oppose the pro-China curriculum. It was called Scholarism, you know, scholar activism. Get it?

Here is Joshua aged 15 on a Netflix documentary.

JOSHUA WONG

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7lN9_mQq2mQ

[0:34] What we hope to do is demand freedom of mind and freedom of speech. [0:38]

MIRANDA YIP: Joshua Wong was actually really directly confronting Chun-ying Leung. He was then the chief executive of Hong Kong. And of course in a context where now we know that China wants to you know have a tighter grip of Hong Kong we know that where this is coming from.

HOST: Miranda Yip was a parent of two young children at the time and she became involved in the movement. The movement not only focused on the government, but the schools as well.

MIRANDA: And you know schoolmasters and even you know the whole of the system are kind of the hierarchy that we know that you know there are schools groups that operating schools like the religious group that you know kind of actually have a management of like more than 20 or 30 schools. We talked at those schools and groups and a religious group that might have that decision making so that we influence the implementation rather than we go only to how the policy was being designed and decided by the government.

HOST: The movement couldn’t just rely on targeting the government. It identified any decision maker in the school system that might support the new curriculum, and put pressure on them too.

It’s the kind of decentralised organising you need to challenge authoritarian power. It sounds a little bit like the ‘be water’ approach that the Tiananmen students had identified.

MIRANDA YIP: This is a decentralized organizing strategy and it’s even more obvious in this year in the movement now on the extradition bill that we have seen all this Internet you know using the Internet forum using every single pressure points that you could possibly get to make noise to pressure the targets.

HOST: The movement relied on the traditional mass protest strategy as well. At its height the movement organised a demonstration of 120,000 students and members of the public.

AMANDA: What was the result of all this protest?

MIRANDA YIP: Eventually we pressure the government to put a halt of the pushing the curriculum as a mandatory curriculum that every school will have to follow.

HOST: Miranda thinks it was a moment of political awakening.

MIRANDA YIP: Before that it was like people here in Hong Kong … we just focus on you know how business and trade has been going on in Hong Kong and we were just more care about you know the economic prosperity.

When I first become active in the social movement back in my university No one listen. People were just so strictly focused on their livelihoods and their business lives and and now it is like completely just totally the different picture.

This new generation of young people in Hong Kong are different from their parents’ and their grandparents’ generation. They came of age with Hong Kong as part of China and they understand they are very different from their compatriots coming from the north of the border. They develop a clear strong sense of identity as Hong Kongers.

HOST: Joshua Wong and this new generation of young activists didn’t stop there.

Only a few years later they became influential figures in the 2014 Umbrella Movement which ended up staging 79 days of civil disobedience to call for universal suffrage. Umbrella occupied three sites in the centre of Hong Kong and it had a single Lennon wall decorated with dissident messages made out of post-it-notes.

We have told the Umbrella story before in Episode 12, and in the very next podcast episode – episode 23, we recap some of its important details. Umbrella was another turning point for Hong Kong’s democracy movement, laying bare the intergenerational conflicts that were growing. Umbrella had continuity with the past. It had trusted spokespeople – here the Occupy Trio rather than lawyers – and it used the power of escalation, moving from smaller demonstrations to mass protest action. But it also diverged from past. The biggest difference came from the intergenerational battles that were fought inside of the movement.

A group called the Occupy Trio had a strategy to win universal suffrage that planned to end in a day of civil disobedience in the financial district. But the final stage of that plan never came to be. Instead – a week before the planned one day ‘Occupation of Love and Peace’, students went on strike then initiated their own occupation at the Government Offices. When the student action was met with excessive police force – an occupation outside the Legislative Council began.

So whose occupation was it? Who was in charge?

And even more than ownership – what tactics should the occupiers have used?

Students clashed with police in a way that was very different to those who had experienced Tiananmen.

LEE CHUCK YUEN: There’s some younger generation of protester at that time that do not agree with the Federation of Student Strategy of peaceful demo and or our strategy of peaceful demonstration and they want to fight on the street. If you crash with the police their violence will be stronger than you and you cannot really get anywhere by clashing with the police

HOST: The group also debated the value of staging a long occupation. Occupations come with challenges.

LEE CHUCK YEUN: I think this time we learned the lesson is that to occupy will take a lot of internal wastage of energy. So it would be better to not to occupy. But to be more fluid and to sort of, you know, occupy and retreat, and occupy and retreat, march and retreat, march and retreat. So I think this time is different.

HOST: Umbrella became another crucible for learning. Universal suffrage wasn’t won, but they gained valuable understandings into how to use different forms of protest. Umbrella built on thirty years of protest in Hong Kong and China. Taken together themes emerged. The obvious theme is the power of big marches. But another is the value of decentralised action. In Hong Kong, the movement calls itself ‘water.’ Something Bruce Lee likes to talk about.

BRUCE LEE:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cJMwBwFj5nQ

[0:06] Be formless, shapeless, like water. Now you put water into a cup, it becomes the cup. You put water into a bottle, it becomes the bottle. You put it in a teapot and it becomes a teapot. Now water can flow and it can crash. Be water, my friend. [0:27]

HOST: The idea of ‘be water’ can also be traced to the democracy movement in Spain in 2012 where they use the phrase liquid democracy. Like the ideas of the Tiananmen students in June 1989, the 2019 movement seeks to flow and move across Hong Kong and not be tied to a single place. Consequently that July and August every MTR train station has been decorated with a Lennon Wall. There was an explosion of new local democracy groups and alliances that were organising events and action almost every day.

REVEREND CHU: Today’s movement has developed into something that penetrates neighbourhoods, every community has their own template and tactic, while all of them still remain peaceful and non-violent. The only violent encounters or scuffles are all instigated by police, stemming from them pursuing peaceful protesters with force and violence. So the movement today is better than what came before in 2014 and also in 1989. We are not static or stationary in one place – everyone is acting according to their strengths and talents. Everyone is unleashing their own unique talents and this is what you see in the “Lennon Walls”, other special activities, taking out ads targeted at the G20 in international newspapers – these are all new tactics of resistance. I believe that this has evolved into a better movement – so we implore them to not get arrested, to not shed any blood, to stay safe.

HOST: Umbrella also revealed how hard it is to win universal suffrage. But even more than this, it raised the question of whether one country two systems can work. As Angus Hui noted on Talking Politics.

ANGUS HUI

https://www.talkingpoliticspodcast.com/blog/2019/172-hong-kong

[9:03] The failure of the Umbrella Movement showed that the Chinese government is not going to give genuine universal suffrage to Hong Kong, so the only way for Hong Kongers to get genuine democracy is to get rid of China. And that’s why they just believe independence will be an option. [9:30]

HOST: New more radical, separatist narratives emerged after Umbrella, and they are present in today’s Extradition movement. Instead of the mainland solidarity that spurred the Tiananmen protests, many in today’s demonstrations call for detachment from the People’s Republic of China. But beyond these postures, the 2019 generation – which is different again to scholarism and to the umbrella activists – are growing up fearful of 2047 and the return of Hong Kong to Chinese rule when the Handover agreement ends.

ANGUS HUI:

https://www.talkingpoliticspodcast.com/blog/2019/172-hong-kong

[12:30] The youth refuse to trust the one country, two systems. In the 1980s, actually Hong Kong citizens were not allowed to get involved in the negotiations. That’s why, for us, the Hong Kong youngsters, we don’t believe the one country two systems or this Sino-British joint declaration represent us because we don’t have the right to represent our views during the negotiation. So why do we need to recognise the joint-declaration? [13:20]

HOST: Faced with this uncertain political future, it is not surprising that the Hong Kong people are pushing back. It’s an existential fear.

HANS VAN DE VEN

https://www.talkingpoliticspodcast.com/blog/2019/172-hong-kong

[4:13] This is not going to stop… the stakes are much higher than just this law. There is a sense of martyrdom. People have killed themselves… People are willing to sacrifice their lives for what they’re fighting for… this isn’t just a fight about an extradition law … it’s much more important than that. [4:49]

HOST: While the world’s attention has locked on Hong Kong in 2019, these modern protests have been shaped by the weight of battles that have come before them.

And the most recent and influential of all these battles was the 2014 Umbrella Movement and what happened in its wake. This is the focus of the next episode.

The challenges of Umbrella raised the question – will people gather again to fight for democracy given they didn’t win during Umbrella?

On the 9th June when 1.2 million people marched against the Extradition Bill – that question was answered.

MIRANDA YIP: I remember when I was in the June 9th rally. And when we were walking towards the area where the Umbrella Movement you know we occupy that area for 79 days and I remember so clearly. I was actually in tears when we were walking in the area I remember you know how moving it was. It makes you feel that that the spirit has come back, the spirit the Hong Kong people have come back we have come back. we had this slogan we we write on the wall we write on the wall that we will come back you know indeed. We come back.

HOST: Changemakers is hosted by me, Amanda Tattersall. Remember to subscribe to this podcast to catch all our episodes. This Changemakers episode is produced by Samuel Chu and Amanda Tattersall. This episode is written by Mark Isaacs and edited by Amanda Tattersall. Our audio producers are Jules Wucherer.

Our sponsoring organisation is the Sydney Policy Lab at the University of Sydney. They break down barriers between researchers, policy makers and community campaigners so we can build change together. Check them out at sydney.edu.au\policy-lab. We are also supported the Organising Cities project funded by the Halloran Trust based at the University of Sydney.

Like us on Facebook at changemakers podcast, follow us on twitter at @changemakers99 and check out changemakerspodcast.org for transcripts and updates on all our stories.

And don’t forget to register for one of our MasterClasses if you want to take a deeper dive into the art of ChangeMaking.

Join our weekly email list to hear our latest musings, podcasts and training. Click on this button to subscribe: